Genre of the Day - Tone Poem

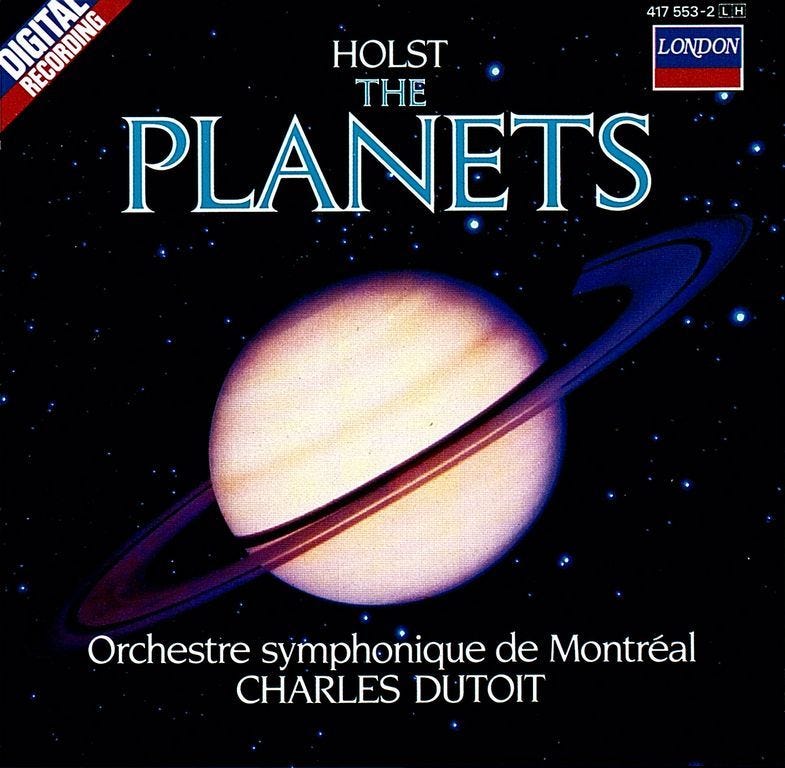

Album of the Day - The Planets by Orchestre symphonique de Montréal / Charles Dutoit, composed by Gustav Holst (composition 1918)

After a weekend of glee and frivolity, I had to set to work today as Sundays often go. I was tasked with completing 360 pages of reading, possibly the largest sum of reading heaped upon me within one week, of an exceedingly dense book. Richard Rhodes’ The Making of the Atomic Bomb delves into nuclear physics' history with exhaustive detail; it’s a fascinating, ambitious read equally thought-provoking in philosophical and scientific explorations. After hundreds of pages, my brain feels as if it just gorged on a feast, crowding out any personal thoughts. As they say online—head empty, no thoughts. Nonetheless, after reading about all that these physicists pursued as Renaissance men simultaneously doggedly pursuing their scientific inquiries—Oppenheimer apparently took five classes and audited four more at a time—the least I can do is complete my little daily musical project. It’s pertinent, then, that we get a genre that feels particularly grand and ambitious in scope.

Tone poems presuppose music as a phenomenon that inherently engages the visual imagination. Though 20th-century folk genres like canto a lo poeta often engaged with poetry, to do so in an orchestral, non-lyrical context is more conceptually difficult and bold. They came about as a musical manifestation of 19th-century Romanticism’s proposition that all means of art were expressions of the unconscious and emotional. The idea that music has mimetic value, evoking that which we see in the real world, was reputed by Aristotle and Plato. Tone poems apply that ideal for its era of western classical music in which Romanticism-inclined composers began to conceptualize music as a conduit for other forms of art, building upon each other to evoke a visual in sound.

The Last Day of Pompeii, a Romantic-era standout.

Tone poems, as the name would suggest, most often drew upon poems as a source of external compositional inspiration. In their vividness and applicability to individual interpretation, poems make the most sensible analogs to music, but tone poems also made use of short stories, paintings, and plays. In prompting listeners to focus deeply on their imaginative and emotional capacities stimulated by music, composers prophesied the concept of a film score before the technology to connect sound to moving image was a glimmer in anyone’s eyes. Tone poems also feel revolutionary in their emphasis on the individual, intimate musical experience; everyone envisions different scenes when struck by sounds that resonate, an inexplicable and deeply mystical phenomenon. Composers like Franz Liszt, Bedřich Smetana, and Antonin Dvořák spearheaded the development of tone poems; Smetana based one off of a river he was particularly fond of in his native Czechia, and the fellow Czech Dvořák wrote several inspired by the folkloric poet Karel Jaromír Erben. Tone poems’ adoration for place also speaks to a uniquely burgeoning 1800s sense of patriotism emerging across Europe in many pieces’ evocation to folkloric nostalgia.

Gustav Holst’s The Planets has been said to be the most famous classical work produced in Britain, a country not particularly known for orchestral glory; it seems it required astrological inspiration to discredit the naysayers. Holst penned evocative pieces inspired by apocryphal gospels and Sanskrit epics, but his most enduring work was inspired by looking to the cosmos. Each suite in The Planets distills the astrological character of our heavenly bodies with an emphatic sense of drama. Mars, the planet of action, sweeps in with enveloping launches into full strength and an ascent into battled frenzy via awe-inspiring stabs of strings and timpani drum clamor so wide and terrifying they roll over the listener entirely. Venus is a welcome shift into gentle fluidity, tender violin, flute, and celesta painting watercolor tones of beauty. Mercury is appropriately a scherzo, a short and fleet-footed piece bringing about levity and aspiring to efficiency as the planet of communication. The most famous piece, Jupiter, begins zippy and rousing before waltzing into vivid sonic regalia as the astrological representative of growth. Talk of Saturn returns and their implications for those headed into their 30s has abounded this year, and the planet’s emphases on discipline influence a rather stern composition with looming harmonies rather than flowing melodies. There remain two more planets on this musical spaceship’s routes, and the final passage of closing Neptune speaks to something divine in humanity and human in the divine as a celestial female choir guides the listener to cosmic ascendance.

IF YOU LIKED THIS GENRE: Zeuhl, Gamelan semar pegulingan, Romanticism

I have no clue how you do it. I haven't written in two weeks because I was recovering from an intense series of concerts. I wasn't even performing, just attending! Thank you for the background on The Planets. Growing up I had heard some of the pieces, but never put them in context. I do know that I liked Holst more than Gershwin, who became much more famous but who is a bit too maudlin for me.