Genre of the Day - Pansori

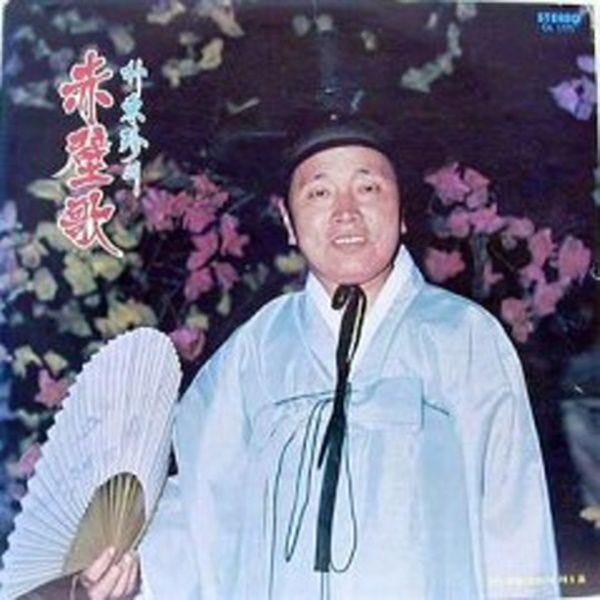

Album of the Day - 적벽가 by Park Tong-jin (1974)

June 15, 2024

If you stretch the definition of show tunes to an extreme, today's genre is technically just a form of show tunes, the genre I covered in yesterday’s article. Actually, translating the Korean word pansori would tell you as much: pan means a place to gather (a show, no?) and sori means sound. Welcome back, show tunes! While the show tunes I covered yesterday require a village of songwriters, performers, set creators, and dancers to bring them to life, pansori strips storytelling music back to its barest individual form. Not only is it minimal, its intensity is just as gripping and immersive as show tunes; pansori performers, who carry out the show by themselves with only a drummer to accompany them, stretch themselves to the limits for the story at hand for hours at a time. They better have those vocal honey chews ready.

From gugak to jeong-ak, the music of Korea’s antiquity is often defined by a penchant for minimalism and negative space, pervaded by sparse drumming and nuanced instrumental explorations. Pansori follows that template instrumentally while filling the bulk of the space with a constant flow of words. Pansori dominated Korean entertainment at aristocratic events as well as popularly from the 1600s to the 1800s. In performing its lengthy tales in the form of twelve key traditional pansoris, performers must maintain a “consistent and constant effort” measured by the concept gongryeok if for a moment they falter in bringing the expected exaggeration and unbridled emotion asked by the form. If they knocked it out of the park, their gongryeok was high. A drummer called the gosu accompanies the singer with some seated support via the soribuk drum with a thick, dramatic oomph.

Pansori is rife with insights into Korean traditions before Westernization, which is why the South Korean government finally began to recognize its importance officially in the latter half of the 20th century as a country weary of decades of cultural infiltration by outsiders harkened back to its rich traditions. It’s a fantastic representation of the arduous dedication to effort and mastery of form idealized by Korea’s Confucian history. Plus, while musically worlds apart—pansori was not particularly preoccupied with hip-hop—pansori mirrors today’s K-pop in the grit and utter determination demanded of both genres’ performers, as discussed by Myung-Sook Auh.

I don’t know if one pansori listen qualifies me to judge gongryeok yet, but I’d reckon it’s safe to say that Park Tong-jin has a boatload of it. In revitalizing the traditional form for the 20th century after Western influence had flooded Korean musical output, Park Tongjin transformed it into a greater spectacle and drew audiences in by freely exchanging conversations with his drummer during performances and adding creative spins on the delivery of the lyrics. His powerful voice anchors this improvisation as he excavates these old stories, ensuring that he never misses the mark on the form’s bombast and emotional leaps and falls. Today, he offers us a glimpse of a pansori about the Battle of the Red Cliffs of ancient China. The pansori maintains an eternal appeal because of its gripping view of what war is like for ordinary soldiers rather than idealized heroes, starkly detailing being burnt, raped, or maimed by the enemy and longing for far away families at home. It’s a surprisingly unflinching view, and a reminder that while we often look back at our ancestors as battle-hungry, battle-weary tunes have always resonated widely. This two-part album is filled with impressive trills, capturing high notes expressing raw anguish, and theatrical bombast, an astounding feat of individual musical effort as much as a pertinent statement on war’s pitfalls. BLACKPINK solo pansoris when?