EVERY GENRE PROJECT - March 24 - Jeong-ak

Genre of the Day - Jeong-ak

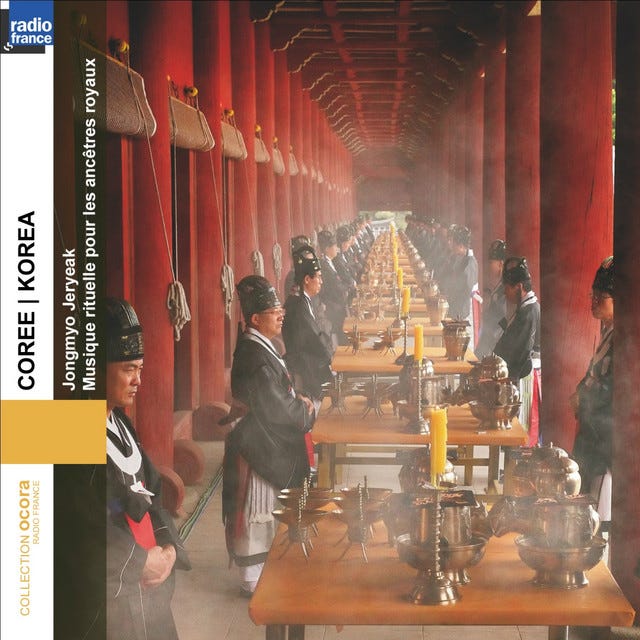

Album of the Day - Korea: Jongmyo Jeryeak (Ritual Music for the Royal Ancestors) by Orchestra of the National Gugak Center of Korea (2011, composed in the 15th century)

March 25, 2024

I wonder what ancient royals would think if they knew that any common folk could hit a button and enwrap themselves in the same music that was once sacredly kept to the hallowed confines of their courts. Enraged? Curious? At this point, my talking point on this column is that the biggest realization I’m confronted with daily now is how much of a full-senses experience music is, that the experience of listening represents only a small cross-section of the matter. Today's genre in particular lays that bare: though I listen earnestly, I am not a Korean royal, and I can only imagine how it felt to have these songs presented to my highness hundreds of years ago.

Not only that, but RateYourMusic and the internet have a particular dearth of information on jeong-ak. Thus, my detective abilities have to kick into full gear. To this day, Korean society is extensively hierarchical, especially down to corporate culture. This is mostly due to its nature as an insularly homogenous culture confined to one relatively small peninsula, a lengthy history of Confucian ideals, and a strong class of nobility. This is a problem modern Korean society is actively trying to tackle to create a more equitable climate—such as through this silly PSA. However, it’s been in existence for hundreds of years, and thus an entire type of music being reserved to that upper class existing back in the day is a given.

Today we tackle jeong-ak, a form of aak—the general word denoting regal music. Jeong-ak translates to “proper music,” so today we get a lesson in how music should sound according to the royal court’s best composers. This lengthy album reserves nothing in exploring the full range of jeong-ak with a hefty 27 songs. Most of the songs work themselves in as part of two suites. The botaepyeong songs mean achieving great peace. The subsequent jeongdaeyop portion extends the glory of the royalty’s abilities as it translates to achieving great works. Like military music, this music is both a stamp on the nobility’s greatness as much as it is an artistic tool to motivate the continuation of that glory.

Musically, the songs here have a mesmerizing sense of both tranquility and gravity. They advance at a drawn-out, almost meditative pace: one can understand why that sense of slow calm would be particularly suitable for royalty and the sense of intellectualism that would’ve set them worlds apart from their subjects. Throughout the botaepyeong suite, the booming drum, subtle chimes, buzzing horn, and deep-voiced choir set an intense and austere tone. With the songs of the great works, the jeongdaeyop suite, there’s a shift to a brighter sound and the horn is more sailing than commanding, spurring a sense of motivation and achievement. While most music implicitly or explicitly is played for a purpose, there are few genres with as much self-ascribed gravitas as this. The intensity and meticulous attention to detail align seamlessly with that aim. You may need to close your eyes, but with the help of this album, for around an hour you can feel like the king of Korea, or maybe the duke of Koreatown at least.