Genre of the Day - Sungura 🇿🇼

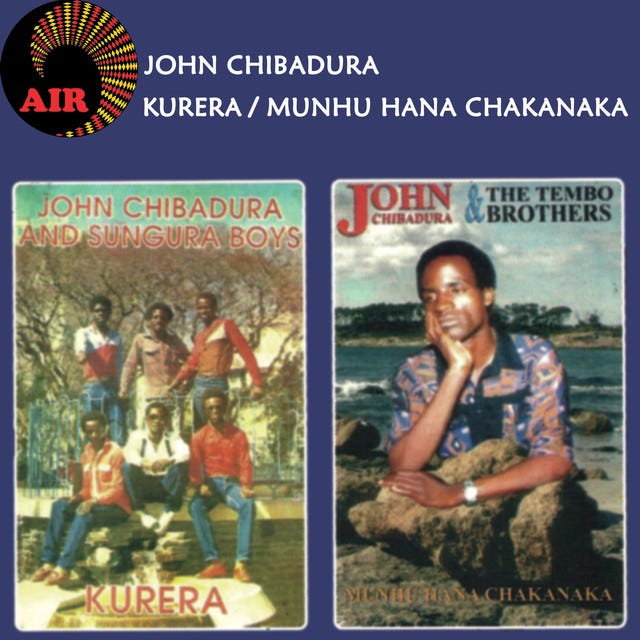

Album of the Day - Kurera / Munhu Hana Chakanaka by John Chibadura (1985)

July 21, 2024

Today’s genre offers a veritable Tale of Two Genres for this column, if London and Paris were Harare and Bulawayo. We’re stopping in Zimbabwe again after having been graced by jit a couple months back. While amapiano’s ascendance is fostering renewed global interest in southern African popular music styles, the current global conversation around African music is still mostly centered on west Africa’s Afrobeats powerhouse names. Let’s take it back in time a few decades ago when all eyes were on Zimbabwe, Zambia, and South Africa’s canopies of musical styles. That being said, today’s genre is also a testament to the power of intra-continental musical communication in the past century birthing vivid local amalgamations of styles.

Sungura evolved in parallel to jit in Zimbabwe’s freshly independent 1980s, and features some of its same stylistic hallmarks derived from chimurenga, a confrontational political genre musically predicated on the transposition of mbira thumb piano scales to electric guitar melodies. One clue to their difference lies in the name: rather than a word in any language of Zimbabwe, sungura means rabbit in Swahili. Though cute, the rabbit part doesn’t matter as much as the Swahili storyline. As this lovely, comprehensive blog dedicated to sungura explains, it’s a sound steeped in momentary escapes from mid-century struggles for liberation and wars. In the ‘70s, independence fighters from southern Africa were taking refuge and training in Tanzania. Benga records, a Kenyan genre fusing the strong rhythms of Congolese rhumba mixing with local staccato electric guitar melodies (parallel to omutibo’s dry-guitar) soundtracked their downtime. Many of the records they were listening to were put out by the Kenyan label, Sungura.

Upon returning to Zimbabwe, some of the soldiers started bands like the Kassongo Band and fused the sounds they’d loved abroad with local styles, though with more outside influence than jit. Naturally, the best way to honor their time in Tanzania was to name the new sound after the label. Sonically, sungura was poised for commercial success by bridging the gap between the rumba-derived soukous long popular across the country with equally popular, bassline-emphasizing South African jive and unfamiliar touches by way of the benga influence. Zimbabwe successfully gained independence in 1980.

As the sense of political urgency that had driven chimurenga’s direct lyrics declined, sungura pioneers strayed away from a direct political path and led with more subtle, idiomatic commentary refocusing their focus towards vignettes of rural struggle, poverty, and heartache. Sungura’s fresh sounds and outlooks, danceable and brightened by particularly high-pitched guitar yet lyrically frank and poignant, helped define the transitional experiences of the thousands migrating from rural areas to Zimbabwe’s cities. It’s been pointed to as the most academically underdiscussed yet most nationally beloved Zimbabwean musical style.

John Chibadura was born to two Mozambican parents who were laborers in Zimbabwe, reflecting how just as sungura adopted a variety of African sounds in a new national Zimbabwean context, some of its early stars had personal stories that existed beyond borders. He led a group that fancied themselves the leaders of sungura as the Sungura Boys, before departing after a few years to front another group known as the Tembo Brothers. The Tembo Brothers went on to tour the UK at the peak of the ‘80s appetite for so-called ‘world music’ acts like the Bhundu Boys, though with a much less tragic ending. This set covers compositions from both acts.

The guitar here indeed sounds a touch sharper and brighter than the jit I’ve heard; the basslines and lead guitar melodies opener “Kurera” leap and bound in interlocking, perpendicular planes, rhthmically anchored by subtle yet effective rapid hi-hats. Though he sings his heart out on tracks like “Maggie Mukadzi Wangu,” the bass is busy to the point of distraction; it’s hypnotic to study its unconventional, persistent jumps. The tension between the oft-sorrowful Shona lyrics and the bursts of staccato guitar energy isn’t evident sonically for a non-speaker, but it simmers in the passionate vocals. Transitioning to his time with the Tembo Brothers, the guitar voicings are a tad softer and the soft beds of vocal harmony on “Munhu Hana Chakanaka” are a slight departure, though the melodies are still busy and fizzy. These songs read more jit-adjacent, especially with the harder drum beats and synth touches of “Zano Rako Mukuma.” Read as a whole, it’s an excellent documentation of how innovators harnessed guitars to redefine the country’s identity in its first independent decade through music that both spanned the African continent’s sonic declarations while speaking to a distinct Zimbabwean experience.