Genre of the Day - Omutibo

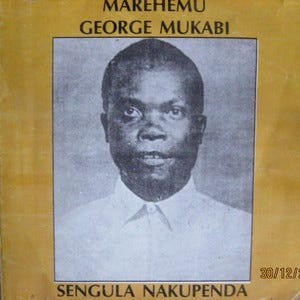

Album of the Day - Sengula Nakupenda by Marehemu George Mukabi (unknown year, pre-1963)

Should we feel sympathy towards an instrument? Arguably not—the acoustic guitar is still one of the most-played instruments around the world. Nonetheless, today’s genre’s story is a sketch of how even innovative forms of music can get swelled up and washed away in the rising tides of modernity. Omutibo’s reign as Kenya’s guitar music would get kicked aside by the dazzling appeal of the electric guitars once they hit the market. Eventually, though, the tide of new crazes recedes. Despite the storms that left omutibo vacant as a form until a recent revival, the ebullient sounds of today’s genre float weightlessly above those storms thanks to the precious magic of recordings.

While urbanites often discover their favorite musical mingling in clubs and bars, today’s genre is proof that the sweet sounds and balance of rootsiness and versatility of the acoustic guitar is perhaps the country’s ideal soundtrack—not just in the US but across continents. Coincidentally enough, the bull-fighting tradition in the Kenyan county of Kakamega where omutibo hails from is not unlike rural America’s beloved rodeos.

As in other African guitar-based genres like jit, the instrument acted as a novel sound outside of Kenya’s urban centers and a versatile blank slate to interpolate traditional melodies and accompanying dances. Today’s artist Marehemu George Mukabi was one of the rare musicians truly deserving of the accolade pioneer, as he kickstarted omutibo nearly singlehandedly after having been taught the guitar by a man in the village of Khayega. The genre took off in the 1950s first among the Luhya people of his local area, made up of nineteen tribes who were politically integrated together in the 19th century, before becoming a national mainstay in the ‘60s before electric guitars became king.

While he may have started a craze for the ‘dry-guitar,’ the local term for acoustic guitar, reverence for plucked stringed instruments was far from unfamiliar territory for the Luhya. The seven-stringed lyre called the litungu was integral to Luhya music, so players adapting to the guitar were already poised to do so smoothly. They had to adapt to a wholly different position of playing, as the litungu is played on the player’s lap or on its side lying on the ground—but, as with Elizabeth Cotten who featured on Piedmont blues, coming from a different instrumental background only enhanced the music thanks to adapted muscle memory configuring fresh ways to draw sound out of arguably the most versatile global instrument. Omutibo merged the melodic and rhythmic capabilities of the guitar in a robust, bouncy way with rhythmic buttressing by simple bottle-playing.

Today’s artist's life uncannily begins and ends with the guitar. Mukabi was fiercely protective of his performances and his craft, and he kept a knife on him lest anyone interrupt his shows, a considerably more intense method to ensure silence than Lorde’s memeified shushing of the crowd during performances of “Writer in the Dark.” He wouldn’t hesitate to die for his craft—and when his second wife accidentally broke a string of his favorite guitar, he chased after her to her parents’ house and attempted to attack her. The woman’s father, too weak to fight Mukabi himself, rallied the neighbors who rained down a storm of machetes on the musician. It strangely mirrors the demise of Don Giovanni, the subject of yesterday’s article, but with a vastly different cautionary tale—love for music can be just as potent as romantic love, and in rare instances as dangerous. So never risk a machete attack over a simple broken string. It’s funny how metal can entrance us with beautiful sounds as strings while also glinting as the blade of a sword.

Despite the dismal tone the story of Mukabi’s death might cast over his music, his astounding development of bass, rhythmic, and lead melodic lines simultaneously with just one guitar and simple-but-effective rhythmically deployed glass bottle is jubilant enough to overcome it. His Swahili singing is clipped and he rarely lingers on notes—one can only imagine that he was attuning most of his attention to the complex layers he was developing at every given moment of his compositions. From the softly rosy sonic textures of “Bibi Mzuri Nyumbani” (translating to “Good Housewife,” and now a song I found beautiful comes off as all too spooky) to the springy bloom of “Asante Kwa Wazizi,” (“Thanks to Wazizi”) Mukabi proves his right to be crowned as the giant of Kenyan guitar even despite all the acoustic and electric imitators who have come since. I assure him, beyond the pale, that I would still think this without the potential threat of a knifing, a testament to his singular stylistic and instrumental mastery.