Genre of the Day - Gondang

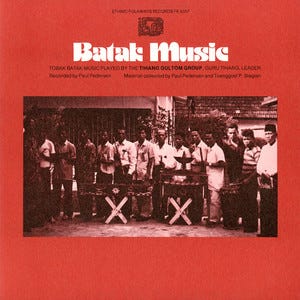

Album of the Day - Batak Music by Tihang Gultom Group (1976)

Today, I was lucky enough to indulge in a rare hike up in LA’s mountains. Amidst our time driving and in nature and in the context of the hike being with a professor and fellow students, I was finally able to reflect more about where this project is. It’s always hard to zoom out while you’re still in the midst of something—I’ve been learning that well in other parts of my life recently. But I know that at the very least, I’ve leapt forth in my knowledge of Brazil, Cuba, and Indonesia than I did prior to this year, as each of those three nations possess a particular abundance of genres documented on RYM and particularly vibrant centuries of musical precedence in conversation with global musical trends but with an insular richness wholly their own.

Gondang hails from the ceremonial traditions of the Bataknese people of northern Sumatra, the Indonesian archipelago’s western-most major island renowned internationally for its coffee, second in fame to ubiquitous Java coffee. Its musical traditions are as elemental as the volcanic soil feeding its coffee beans. Is Quora a credible source? Notoriously, it is not. But as a window into anecdotal insights, it’s excellent. One Quora response from a Javanese user to a question about the Bataknese people sings the culture’s praises with an omniscient tone, noting that “you need one Bataknese in your life to complete your journey!” Not everyone in the world may be so lucky, numbers-wise, to have a Bataknese friend, but I’m glad we will be fulfilling a Bataknese genre in this column.

A Lake Toba Batak house, one of Indonesia’s most awe-striking architectural traditions.

Gondang drums are set apart among the leagues of drums peppering the archipelago’s classical ensemble traditions by their unique tone systems. These five drums are tuned slightly differently, reflecting a synthesis of rhythm and melody also found in traditions like Yoruba talking drums. A large bass drum, the gordang, a few gongs, and an iron percussion plaque round out the rhythmic center driving the sarunai melodies, an instrument similar to the oboe. The cycle of typically seven gondang pieces act as ceremonial nods to the traditional Batak gods, music carrying forth religious traditions that have only officially become displaced by Christianity and Islam but culturally persist. The performance of gondang music symbolically helps the ensemble’s leader, a medium of sorts, act as a conduit for ancestors. Over time, these stricter aspects of gondang music like the seven cycles have given way to less structure to maintain their survival at a variety of traditional events and social gatherings; nonetheless, its instrumental integrity remains the same and retains its unique rhythmic tones.

A spoken section introduces each element of the ensemble—the oboe and the flutes receive particular attention compared to the drums that academically are noted to set it apart, but percussion often moves in subtlety anyway. A closer listen engenders further appreciation. The drums occasionally stop the ensemble with a commanding certainty as in the “Song of the Babysitter,” a generally gentle and light-natured iteration of an instrumental ensemble per wider archipelago standards, a parallel to gamelan semar pegulingan. Though its name may throw you for a loop and prompt questions about the ancestral storylines being played out, “Song of the Ugly One” condenses the ensemble’s sound with rapid-fire speed, the drums acting as polyrhythmic mercenaries. “O Aek Sarula” slows the instruments to allow for resplendent vocal harmonies, a testament to the synergy within Batak instrumental ensembles not unlike the unique contribution of each slightly different, fine-tuned drum.