Genre of the Day - Pashto Folk Music

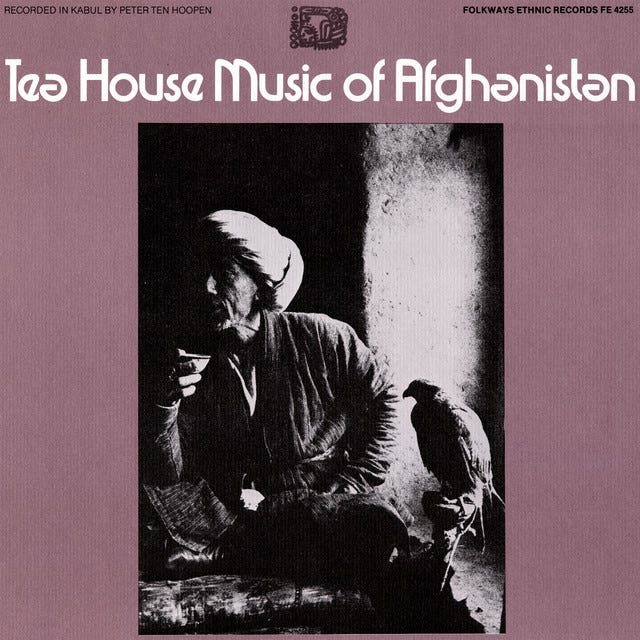

Album of the Day - Tea House Music of Afghanistan by Various Artists (1977)

Whether economics or the study of music qualifies as a better way to understand humanity colors my thoughts as I set out to embark on today’s genre. Economics is contested to be a study of human behavior, but as I’ve increasingly deepened my knowledge of music across various human planes of existence this year, I find there may be no better way to understand the human experience. Perhaps this may seem a non-sequitur, but I am sitting down to write after an awesomely long study session with my friend in my class about free trade, and we found that the tenets of our class often spoke well to personal situations through some stretches of the studying imagination. Music is an artistic currency, and Spotify—though streaming comes with as many arguments against it as free trade—has helped me diversify my portfolio a hundredfold.

If not economics, music at least helps clarify our pictures of countries and help indulge us in a richer, deeper history of places with complicated political paths rather than CNN’s takes. The Pashtun people are the dominant group in Afghanistan, though northwestern Pakistan is also home to many. For centuries prior to its 20th and 21st centuries punctuated by ill-advised, destabilizing military campaigns and subsequent political volatility, Afghanistan has been home to refined poetic and musical forms in the Pashto language, spoken by 80 million people today. This history is still reflected in modern institutional symbolism; Kabul is home to Rahman Baba High School, named for a Sufi poet so beloved by Pashto speakers his works are considered second only to the Quran. Just like today’s album, a tragic translational barrier confronts my journey to understand his quotes selected for this YouTube video, but if any Pashto speakers ever frequent this blog, do let me know his thoughts.

Instrumentally, Pashto folk music is firmly placed within the continuum of southern Asian folk music. The rhythm section employs the tabla and dhol drums that characterize and add such tonal color to much of south Asian music, though the rubab lute acts as a unique symbol of national pride. As is appropriate for its poetic nature, its song forms are what differentiates Pashto folk music the most. The charbetta is an epic form exalting heroic figures. Neemakai explores the daily lives of Pashto women in short vignettes. Loba positions men and women in a romantic duet. Tappa poems are similar to a haiku, only truncated, with one shorter line and a longer follow-up. These stilted stories number in the hundreds and thousands, acting as casually poetic observations tossed around in conversation. When set to song, it’s applied in a variety of 16 musical modes and instruments.

گلونه ډېر دي خداى دې ډېر کړي

د صبر گل به خپل اشنا له ورکومه

The garden is full of flowers but I have to present the flower of patience to my lover.

The Taliban has been diametrically opposed to the proliferation of Pashto music since its fullest stranglehold over the country began in 2021. Contrary to hundreds of years of vibrant history, the group has decried music as idolatrous and sinful, burning instruments. Thus, Pashto folk music has had to quietly retreat from view, surreptitiously sounded at small gatherings, in basements, and by oneself. The swift rubab arpeggios opening “Come to me in the morning” bear a certain melodic majesty that draws one back through the halls of musical memory; this album just barely predates the beginning of the country’s half-century of turmoil. The album is a bit strangely mixed; it’s a fascinating, occasionally disquieting, unintentional dissection showing each element of Pashto folk music in full asynchronous clarity: “Traditional” (in Pashto) indulges you in a man’s voice on the left and the rapid-fire poppings of dhol on the right. The verbal passion for poetry is evident in the yearning vocals of “Come with me to the priest (to get married),” love’s urgency underscored by the tonal richness and speed of the music. Music is too fluid a force, and its history too strong, to ever be stamped out even by those hostile to the joy it brings. One hopes that a critical juncture can come to pass that will bring down the factors harmful to human life and Pashto cultural expression at the moment, and that music can be a reminder of beauty.

I like #7 very much