Genre of the Day - Yé-yé 🇫🇷

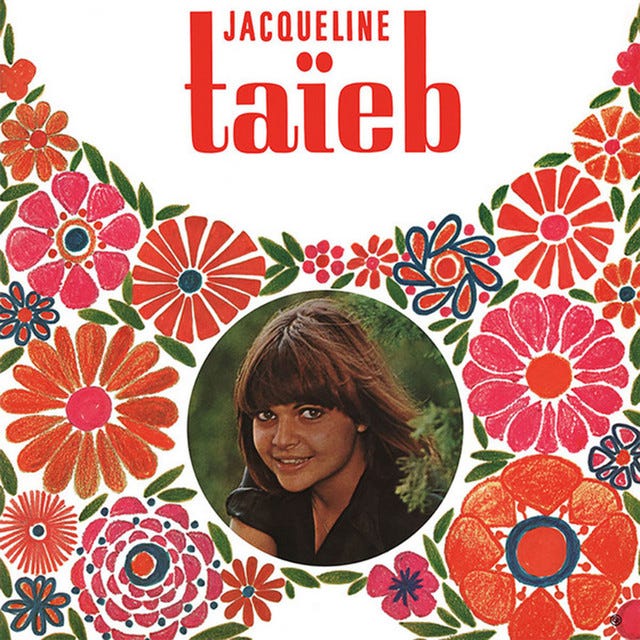

Album of the Day - Jacqueline Taïeb by Jacqueline Taïeb (1968)

Nonsense is one of the most iconic lyrical tools in popular music. Na na nas, la la las, and heys carry singers’ voices extending past the boundaries of different languages and, despite having no evident verbal meaning, listeners implicitly appreciate the melodic charm. Jùjú, a catchy and alliterative name yet also an excellent nod to the melodic lilt of the talking drums that define it, was one genre-level example of the phenomenon. Yé-yé music, though, is both a meaningless Englishism of the late ‘60s French environment that precipitated the iconic pop genre as much as a forward-marching, insistent statement of purpose.

Like yesterday’s twee pop, the aesthetic background of yé-yé has remained fashionably beloved, but it was a kindred musical spirit in repurposing notions of bubblegum sweetness that pop’s detractors often cite into a powerful and salient overtone. Yé-yé emerged in France’s late ‘60s, an epochal moment defined by its post-colonial transition marked by the massive, informal student strikes of 1968 in support of workers, anti-capitalism, and gender equality. The insistent yeah-yeahs—made French and elegant in the e-acute accent—are half fluff and half shout, putting forth a female perspective that, at its best, used pop to its fullest worldly and anthemic potential.

Yé-yé drew on the rock trends of the moment though with an internationalism befitting French youth’s cosmopolitanism in the process of former colonies like Algeria and Senegal gaining hard-fought independence during the decade. Yé-yé was particularly forward-facing in its capacity for movement, drawing from ubiquitous American byways like the twist and light jazz, throwback (by that point) infusions with a mod flair that made it instantly recognizable. Teen pop was a well-established phenomenon by this point across the pond, and similar television revues brought the model to France; some yé-yé singers like “Zou Bisou Bisou[‘s]” Gillian Hills were a sort of cog in this somewhat exploitative machine singing songs of naïveté written by men, whereas others like Françoise Hardy and Jacqueline Taïeb started in the vein of coquette, fresh-faced televised appeal but transitioned to established careers based on songwriting prowess. Voracious, mod, and tongue-in-cheek, yé-yé incorporated both the aforementioned rock and jazz influences with traditional French chanson, bubblegum, exotica, and Baroque influences. This mix of far-ranging influences with its stars’ entertainment power made yé-yé spread like wildfire throughout the mid-’60s.

Tunisian-French singer-songwriter Jacqueline Taïeb won particular acclaim for her 1968 self-titled debut, yé-yé sunshine made timeless by the strength of her artistry and the adventurousness of its sonic landscape. She scales up the strength of her voice to match the massive horn revue of the sardonic on the opener in “Bravo.” Garage rock influence and ubiquitous late-’60s bells and intrigue color “Ce soir je m'en vais,” and other distinctive decadal moments filter through as in the Motown and pysch echoes of “Bientôt tu l'oublieras” and the Doors’ influence of “Bienvenue au pays.” Wider cosmopolitanism influences forays like the daburka percussion paying homage to her Tunisian heritage in “Juste un peu d’amour” and the youthful zeal and inexplicable English-language moments in the hit “7 heures du matin,” her voice quietly trailing off in the fade out as she’s still speaking, the cadence reflecting yé-yé’s televised origins and its tenuous balance between platforming its stars versus giving them a true voice. Make no mistake, though, Taïeb’s deft takes put her voice forth with as much gusto as the genre’s name suggests.

That was charming, but does it really qualify as a genre? Either way, I continue to be impressed with the work you are putting into this.