EVERY GENRE PROJECT - November 8 - Breton Celtic Folk Music

Genre of the Day - Breton Celtic Folk Music

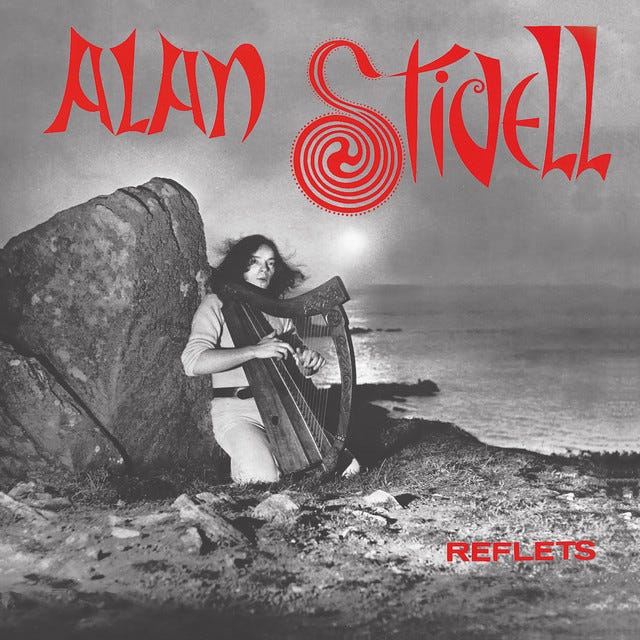

Album of the Day - Reflets by Alan Stivell (1970)

Though music has often been weaponized to legitimize or culturally consolidate the nation-state, it also stands as a tool to subvert the notion of centralization that its creation entails. This has been especially true in France. The long arm of Brittany stretches headstrong into the Atlantic, historically oriented away from the rest of France and more towards its kindred Celtic nations of the British Isles. Though only a few hundred thousand speakers of Breton remained1 by the 2000s, Breton Celtic folk music also represents music’s unparalleled ability to enfold the significance of history through a language, even if not every listener can grasp the actual meaning—an idea that is somehow reminiscent of yesterday’s shoegaze.

Brittany’s Celtic heritage and language were largely subsumed by the Parisian vision of the French nation-state, which depended on the strict institution of the French language to integrate the plethora of cultures from Corsica to the Occitan-speaking south to Brittany. The extent to which the Academie française and cultural purists still fuss over the exact nature of the French used in the public sphere, even in pop settings, speaks to the deeply embedded nature of the French language as an instrument of political adhesion. This was on full display this year amidst the racist rhetoric levied by the French far-right against French-Malian pop star Aya Nakamura this year ahead of her performance at the Olympics opening ceremony, who cleverly responded with a cover of Charles Aznavour’s “For Me... Formidable” poking fun at the critics who’d prefer her to fall in line and only use the “langue de Molière.”

For Brittany, it would take several centuries to accomplish the same assertive musical feat. The peninsula became a province of France in 1532, though with a relatively high degree of independence until facing political and linguistic suppression post-French Revolution. A 1794 report criticized the use of native languages as a “barbaric instrument of [local priests’] superstitious ideas” that was holding backwater citizens in these regions back from loving the Republic. However, the 1950s saw a long-awaited détente in France’s ideas of managing linguistic plurality. The Loi Deixonne was passed in 1951, allowing for education in regional languages and cultures—a marginal advancement in these languages’ protection, even as the state continued to centralize and promise precious few actual protections. Aligning with this new chance at a cultural bloom, the growing global folk consciousness post-WWII spurred Breton folk musicians to harken back to their distinctive Celtic roots and amplify their cultural autonomy in the Breton language.

Brittany’s traditional Celtic music is often performed by ensembles called bagadòu, which paired percussion with the most defining pan-Celtic instrument, the bagpipes. Bagadòus also feature the iconic Breton bombarde, a relative of the oboe. However, the instrument most essential for the Breton Celtic folk music revival has been the harp, which was largely the work of a singular musician: Alan Stivell. Though familiar with all Breton instruments, he was most enamored with the Breton harp that his father had built. As a performing musician, he’s extended his harp expertise to a range of styles, but Reflets is a rich display of the harp in its most unadulterated form. In the stunning opener, sung in French to ease unfamiliar listeners into the peninsula’s artistic world, his harp freely cascades alongside his spectral ululations like the floods of opposition that Breton culture has had to fight against that he alludes to in the lyrics. By the time he switches linguistic modes to his native Breizh tongue as on “Marig Ar Pollanton,” there’s an invigorated quality and openness to his voice. From the waltzing “Suite Irlandaise” to the springy joy of “Tenval An Deiz,” the finely crafted harp sings centuries of Breton persistence, tall and proud.

1 https://langsci.wiscweb.wisc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/1012/2019/01/09-Mendel.pdf