Genre of the Day - Ancient Roman Music

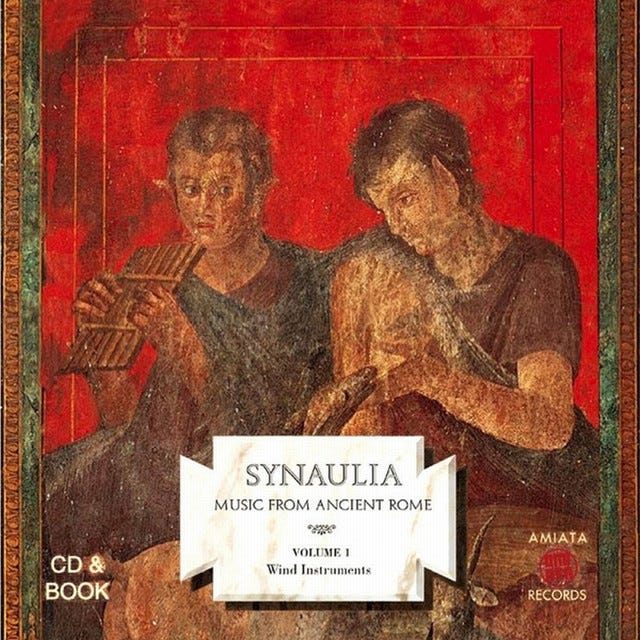

Album of the Day - La musica dell'antica Roma, volume 1: Strumenti a fiato by Synaulia (1996)

Today is Thanksgiving in the United States, and to all those who celebrate, I hope that you had a wonderful day, felt (more than) satisfied by the feast you indulged in, and got to feel moments of gratefulness. Realistically, though, even if Thanksgiving is emotionally centered on, well, giving thanks, how many hours do we spend actually contemplating things to be thankful for over meticulously fussing over, mise-en-placing, and devouring food? If there is any culture known for a lavish banquet, it was Ancient Rome. It’s only right that the ancient civilization’s music claims today’s random genre spot.

Ancient Rome’s shadow looms over modern political, historical, and architectural thought more than it does artistically, relatively speaking in comparison to ancient Egypt and ancient Greece—all roads may lead to Rome, but not all notes. In a culture obsessed with glory and permanence that tenaciously staked its physical right to rule across the swathes of its Mediterranean empire, a more ephemeral phenomenon like music mattered less and thereby rarely factors into the popular imagination of the SPQR today. A lot of men claimed to think regularly about the Roman Empire on social media a year or so ago—where’s the polling on how many wannabe gladiators think about its music? Music permeated several areas of Roman life, though not to the same extent as in Ancient Greece, the civilization’s spiritual progenitor (extremely Latin-looking word) and inevitably the source of musical systems.

The militarized Roman Republic was generally wary of decadence eroding society, so the elite class de-emphasized musical education compared to Greece. Cicero, statesman and stickler, lamented the ability of the “sweet seductiveness of music” to corrupt youth, though he respected select forms as he was well-versed in Roman tragic song. Despite this intellectual skew, the culture maintained a broad class of instruments. In militaristic and ritualistic settings, cymbals, frame drums, and a wooden sandal clapper known as a scabellum provided foreboding rhythms. Wind instruments like the tuba (which actually functioned more like a bugle), the comically long lituus and curved buccina, the aulos double-pipe often used at funerals, and bagpipes were of prime importance. Though surely not as beloved as in Greece, lyres were also present in Roman music. Physical evidence reveals the popularity of street music, as illustrated in murals uncovered from Pompeii and Herculaneum. And even if their purpose was more for spectacle and carnival than for just music, the Romans peppered Europe with amphitheaters that still stand and laid the blueprints for modern-day large music venues.

Though left with few artifacts to draw from, the reconstructions of ancient Roman music by the musical council Synaulia craft a captivating collection using painstakingly recreated wind instruments. The soundscape of “Pavor” is filled with omens, though its whooping and cries paint a dynamic and human picture. These instruments transcend the semantic meaning of the term wind instrument—they sound as if they are filled with the wind itself. The drumming of “Etrura” is not unlike the galloping rhythms of yesterday’s aita, while those playing the winds experiment with intriguing modulation, leaving no stone unturned in imagining how ancient musicians might’ve voiced their instruments. Are the rousing horns of “Arena” not so close to those that herald the beginning of a big night in football—which is a cultural reflection of the other? “Imperium” features similarly on-the-nose, regal trumpets. Lamentation suffuses “Neniae,” haunting wails bringing emotional weight to historical knowledges of elaborate Roman approaches to death. Elsewhere, the crystalline, airy pipes of “Aetherius” and the cultic, surreal “Venus” sound so otherworldly that they may just have flirted with time travel. Thank Jupiter that today our willingness to be more decadent than the Romans allows ardent musicologists to create these compositions that bridge archaeology with music-making’s fluid imagination.

I know we're talking apples vs. Very Different Oranges here, but you might also be interested in the collection of "Roman Songs" from one half of They Might Be Giants:

https://youtube.com/playlist?list=OLAK5uy_nRSSV980V8_msAmHU8Mrs6oV-OVwBHeEQ&si=jWchTJV20j8RNmzX