Genre of the Day - Overture

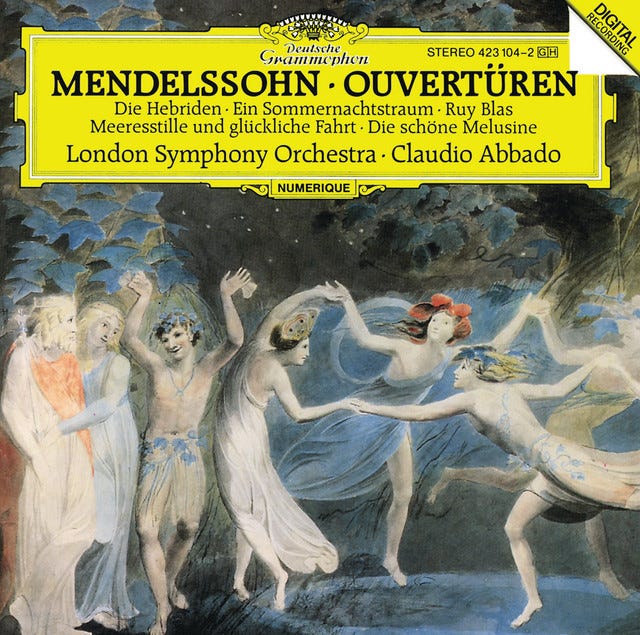

Album of the Day - Ouvertüren by Felix Mendelssohn / London Symphony Orchestra / Claudio Abbado (1988)

The maxim that the first impression matters is a governing factor in many of our life scenarios: we put every hair in place and smooth out a shirt’s every wrinkle for an interview, pull every bit of charm to the surface to dazzle a first date, or craft a lede in the eager hopes that a reader chooses to read a certain Substack article over the tens of thousands of other lovely offerings published on this site each day. After all, as Sade Adu mused on her band’s sophomore album Promise—which, ironically, is just as good or might even exceed the quality of their debut—it’s never as good as the first time. Overtures act as western classical music’s manifestation of the hopes of drawing a listener in from the start of a musical journey.

Overtures were initially pitched by 17th-century composers to better introduce operas and ballets, upping the dramatic spectacle. I know that when the lights dim in a theater and I hear an opening suite, beginning with reticent, quiet flourishes that ascend into full-bodied mini-epics, my senses arise. French composer Jean-Baptiste Lully, who got a shoutout earlier this month in opéra-ballet, anticipated this reaction shrewdly, becoming the first composer to create longer expositions to theatrical works. Lully’s structure quickly caught on as the French ouverture during the Baroque era, consisting of a slow opener in dotted rhythms that flowed into fugal, harmonic counterpoint with a faster pace before drawing back to a slow passage. Sometimes, that slow passage waltzes into a dance form like the minuet—I suppose the complexity of an overture may reflect that of the following spectacle’s story.

By the Romantic era, a growing number of composers played with overtures as standalone pieces. Not only do they provide self-contained narratives, but the form acts as a vignette for how musical languages can become consolidated and communicate certain ideas. As certain leitmotifs (musical flourish that represents an idea or character) became shorthand in overtures, overtures predicted forms like tone poem with similar ideas of how a metanarrative can be expressed through symphonic music. Whether you consider that a beautiful signifier of human communication manifesting artistically or an act of simple, self-explanatory repetition, it demonstrates how creation in every musical form, whether the grandeur of an overture or a folk tune by the hearth, offers a new chance to jump onto the spectrum between innovation and replication and work between these measures.

If there was a king of the overture, few would be happier to be the perpetual opener than Felix Mendehlsson. The German composer’s best-known pieces are his overtures, collected as a series of perpetual exposition on today’s album—cutting out the rest of the stories to follow, though at no loss to these meticulously crafted works. A coherent structure emerges across them, though each does spin a different tale between the overture to A Midsummer Night’s Dream whose rapid-fire, giddy violin cascades aptly depict the escapades and sheer chaos to come, or the decadent flute that suddenly collapses into staccato, passionate string motions so intense they threaten to close in on the overture to Melusine, a precarious tale about a water-nymph disguised as a human. For their loyalty to form, Mendehlsson also literally and figuratively evokes new territory in the Hebrides Overture, an ode to the rugged Scottish archipelago that also directly presages tone poems. It makes good on overture’s name by opening up new horizons for compositional works to transport listeners to novel places in time and space.