EVERY GENRE PROJECT - November 18 - Rhumba

Genre of the Day - Rhumba

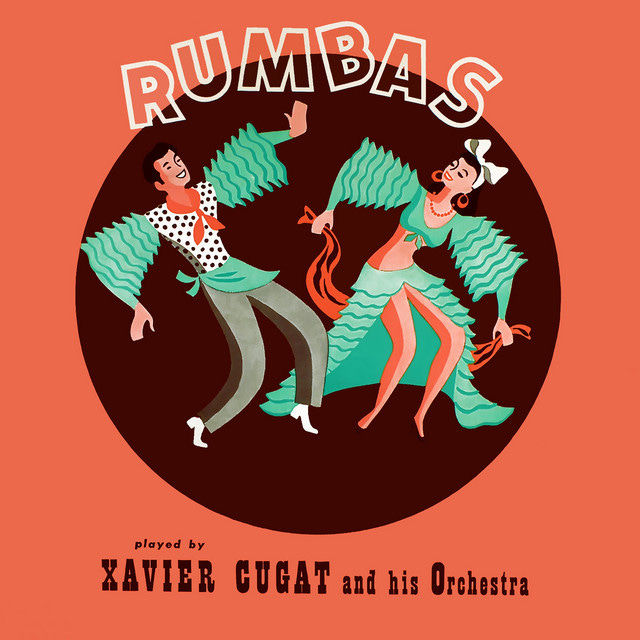

Album of the Day - Rumbas by Xavier Cugat and His Orchestra (1943)

Today, I was lucky to do some field work of sorts. As a part of my college radio station’s music department, each semester the team heads up to Hollywood to peruse a record store to bring some new vinyls to the station. Unfortunately, radio budgets are not exactly akin to the Wicked marketing budget, which is to say that we split into teams of 3-4 people with a budget of $20 each. Alas, I did not get to select a record myself, but gallivanting through their genrekopia was lovely still. Visiting a record store with friends is always a testament to the power of music as you compare and contrast knowledge and tastes in real time. There’s also the way vinyls’ durability holds little histories long beyond their eras—I found several vinyls by today’s artist.

Rhumba marks an early point in an overarching trend of this column, of the constant fluidity of musical communication across cultures since the recording industry began. It’s not to be confused with the more commonly known rumba, although it’s a stateside derivation of the Afro-Cuban musical phenomenon. Last week, I delved into how American popular music began to fuse with Latin stylings in freestyle; inquiry reveals that American musicians and audiences had long been intrigued by Latin sounds, even if the skew was more exoticized. Throughout the mid-20th century, new Latin rhythms became dance crazes overnight regularly, from the mambo to salsa and in rock’n’roll settings like “La bamba.” The presentation of these sounds indicates a certain American naïeveté about these places: one Les Baxter vinyl I found today declared rather nonsensically on its back cover that “the Caribbean Islands form a never-never land that actually exists. Arching from Venezuela to the tip of Florida, they include places whose names have a glow of excitement: Haiti, Trinidad, Barbados, Cuba, Martinique.”

New York City’s growing Cuban population in the 1930s translated to a greater number of Cuban musicians in American scenes, who began to suffuse big band jazz with the country’s distinctive rhythmic and instrumental touches. Don Azpiazú's “The Peanut Vendor” flew off the shelves in 1930, and rhumba bloomed in American ballrooms as dancers shuffled new sounds to distract themselves from economic gloom. It retained rumba’s 2/4 rhythm that made it feel distinctly different from domestic dances like the foxtrot. Other touches were less authentically inclined: vaguely deployed Cuban percussion like bongos and congos was mostly ornamental and gestured towards its exotic origins, while guitar and big band brass maintained the typical jazz status quo.

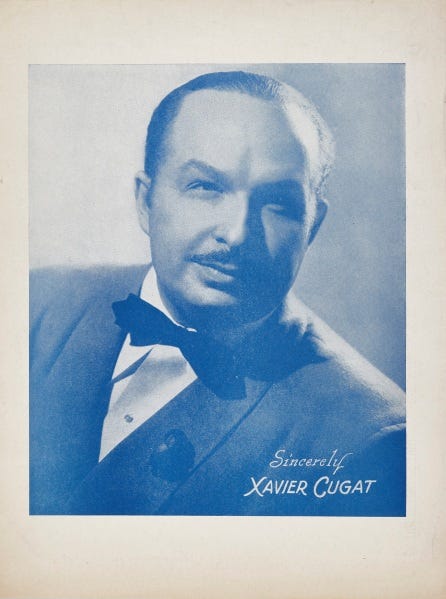

Xavier Cugat was a figure who deeply understood the transcontinental particularities of exporting music as a Spanish-born musician who grew up in Havana before eventually ending up in sunny Los Angeles. He understood entertainment intimately as a friend of Charlie Chaplin and from rubbing shoulders with other stars while operating a popular, splashy Mexican restaurant in West Hollywood. Keenly aware of the importance of knowing one’s audience, he crafted a sound that balanced American jazz sensibilities with the styles he's absorbed coming of age in Cuba and captured the zeitgeist of the rhumba’s era. “My Shawl” features evocative countermelodies exchanged between the canny horns and euphoric piano against the backdrop of rhumba’s surprisingly dynamic percussion. Lulling xylophones and alternating piano and horn solos that recall the development of descarga bask in the lushness of “Green Eyes.” “La Bomba” muses that the rhumba is a “captivating dance in the dark,” expressed in that peculiar ‘40s harmonic delivery that bridges its foreign mystique to dazzling spectacle befitting the epoch. Exoticization notwithstanding, numbers in Spanish like “Havana’s Calling Me” reassert the island’s centrality as a musically enriching wellspring of endless inspiration for musicians and audiences alike.