EVERY GENRE PROJECT - November 16 - Shidaiqu

Genre of the Day - Shidaiqu 🇨🇳

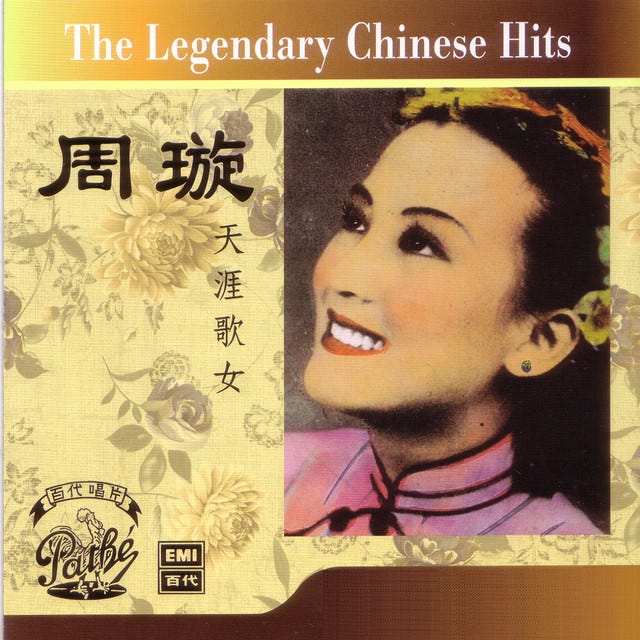

Album of the Day - 周璇之歌 ( 第一集 ) / 天涯歌女 [(Song of Zhou Xuan (Episode 1) / Songstress of the End of the World] by Zhou Xuan (1959)

Although there are so many more things to talk about than school, I fear I am still a student in the midst of setting myself to work for the last stretch of the semester and it inevitably dominates my thoughts. I’m writing a 20-page paper for a class on multinational enterprises, and what else would one choose given my personal writing endeavors this year than a study of the global music industry? China’s music industry largely in a class of its own outside of the global music conversation (though as C-pop shows—not entirely), largely because the state intervenes so heavily in media and it is home to a host of insular streaming services and a robust domestic market, so it’s never really sought to export its musical product as much as neighbors South Korea or Japan. Before this current reality, though, the internationalized city of Shanghai became the picture of cosmopolitanism in China as jazz swept the sound of popular music across the world.

Shidaiqu translates to songs of the era, illustrating its revolutionary representation of modernism in Shanghai. Shanghai had been cracked open to the international commercial sphere by the Treaty of Nanking that resolved the Opium Wars, which divided it into a strange hodgepodge of colonial domination. France operated a slice of the city known as the French Concession, and the UK, US, and Japan co-operated an area dubbed the International Settlement. The surrounding areas remained under Chinese control—how kind of the empires! Suffice to say this among the other humiliating concessions China had to make to end the Opium Wars laid the groundwork for considerable turmoil, but as it brewed, Shanghai flourished musically as a bastion of nascent genre globalization.

The International Settlement, combined with Shanghai’s quick growth as a global commercial center, stimulated the rise of a Chinese music and film industry in the 1920s parallel to the US. Chinese popular song became transfused with influences from jazz and Hollywood musical numbers. Spearheaded by composer Li Jinhui, instrumentation ranged from the classic Tin Pan Alley jazz lineup to incorporating established Chinese instruments. The traditional pentatonic scale was still featured often. A cultural penchant towards numerology is evident in the grouping of the Seven Great Singing Stars who became shidaiqu figureheads beyond the walls of Shanghai’s nightclubs, on records and the silver screen: Bai Hong, Bai Guang, Gong Qiuxia, Li Xianglan, Wu Yingyin, Yao Lee, and Zhou Xuan. Shidaiqi seemed a sickened marker of external subjugation and betraying tradition to both factions sparring for cultural recenterings during the Chinese Civil War, and the genre met its demise during the Cultural Revolution. Its influence lingered in Cantopop, though, in addition to matching the bombast of Crazy Rich Asians’ soundtrack, and represents an early fusion of Chinese musical ingenuity with what the winds of global musical change had to offer.

Zhou Xuan was boldly declared the songstress of the world, which also happens to be the translated title of the first track of this collection of her landmark shidaiqu tunes. On that particular record, her sharp soprano blows off the low-fidelity dust with ease, soaring with emotion over erhu fiddle and pipa lute. Sumptuous Hollywood strings arranged in a jazz waltz beckon the listener to Shanghai’s jazz age on “永遠的微笑” (“Eternal Smile”), her voice underscoring cinematic and plaintive emotion, yet grounded in its performance. Jouncy horns and rollicking banjo and percussion, deeply emblematic of its particular jazz moment as the genre’s translation might suggest, compliments the whimsy of “月圓花好” (“Full Moon and Good Flowers”). Though these songs might sound quaint to us now, they captured the hope that both traditional instrumentation and new musical ideas could capture grand ideas in equal measure, a boundless musical exploration that may have been laid to rest as shidaiqu ceased to define Shanghai’s internationalism, but providing an ideological framework that lives on in Chinese pop traditions.