Genre of the Day - Western

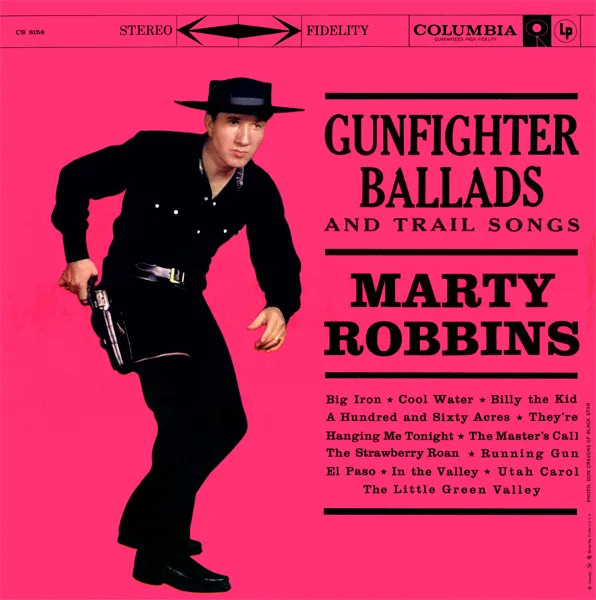

Album of the Day - Gunfighter Ballads and Trail Songs by Marty Robbins (1959)

May 6, 2024

Both yesterday’s genre and today’s reveal musical genres’ power to construct a time and place. As a medium, music is perhaps the art form that indulges most in fantasy. All songs are a snapshot of an idea painted through melodic words and instrumentation. Compare that to film, a medium in which the delineation between truth and fantasy is usually more clear and there’s arguably less to be projected upon by the consumer. Music is a form of longing, for a moment, for community, for love or relief.

Today’s genre deals in that fantasy aspect of music a little more than others, because the American Wild West is a particularly constructed social and historical notion. It’s a place mythical enough to where even people who’ve never seen it helped immortalize it, European filmmakers who were fascinated by its myths and created a gritty picture of the place. The notion developed that brave, strapping cowboys pushed into the region fought back the natives, and through their bloody, heroic exploits they won the west. Growing up in Colorado, my schools never really pushed that narrative. In high school, I actually took a class for college credit on the history of the west, investigating how the west shouldn’t be remembered as a boundary that was gradually beaten back but a dynamic region called the borderlands in existence since Spain’s colonization of what is now the American Southwest, a region composed of a diverse array of interacting groups over time, from indigenous groups to Mexican nationals, white American farmers, Afro-Mexican settlers. Later, the militarized American presence popped up, setting off the Mexican-American War that stamped the west’s mythical fate as—if you skip over the imperial phase where we snatched up Hawai’i, the Philippines, and briefly Cuba—the ultimate chapter in the continental American project. The adage goes that the victors write history, and that certainly applies here.

Western music is a fascinating study because it pairs the sentimentality and value of memory that is integral to country music with the artistically mineable mythics of the west. A lot of that sentimentality comes from the stock of impoverished Scots-Irish and British who flooded the region, integral bodies in the effort to displace the native population. For instrumentation, only that which was portable and wouldn’t weigh the expedition down was feasible. This led to the dominance of the harmonica, guitar, and banjo. Like much music rooted in rural traditions, musicians drew on the simple phenomena around them and brought them to musical life, ultimately influenced by the multitude of people groups in the region: in a piece for the fall 1959 issue of Oklahoma Today, the pioneer in putting western music to record Otto Gray argued that its distinctive rhythms were based on the walking of horses and cows. In a cute creature moment, he also said that the more energetic singing phrases like yippee-yi-yay were employed to motivate the herd in the morning and the more plaintive singing was reserved to ease the herd and one’s own loneliness at night.

Ironically, Marty Robbins’ iconic album that serves as today’s genre figurehead came out in 1960, one year after that same Oklahoma Today issue noted the decline of western music’s commercial presence since its heyday of popularity thanks to the western films of the ‘30s. Robbins was the perfect songwriter and vocalist to revitalize it for a new decade. His deep croon, with just the right amount of sun-weathered roughness around the edges, evokes his ranger grandfather (who inspired the eternal “Big Iron”!) to deftly transport the listener to a recap bonfire on the frontier. It also is a surprisingly representative document in noting the region’s Mexican roots: “El Paso”, one of the album’s best-known hits, finds a protagonist recalling his deadly desire for Feleena, a young Mexican woman, from the beyond. The album, led by pared-back guitar anchored by distinctly ‘50s full-bodied harmonies, is rife with little westernisms like the linguistic quirks of “Strawberry Roan”. Danger lurks around the corner from every triumphant fantasy like “A Hundred and Sixty Acres”, though, such as the hauntingly stark murder ballad “They’re Hanging Me Tonight” (to think this was on a popular music record?!). It’s a construction, but built in tales that are too delicious to not kick back and feel like you’re in a rocking chair overlooking some gorgeous, rough vista.

A huge success in its day, capitalizing on the love America had for the Wild West myth, and establishing Robbins as a leading figure in country music.