EVERY GENRE PROJECT - May 31 - Ranchera

Genre of the Day - Ranchera

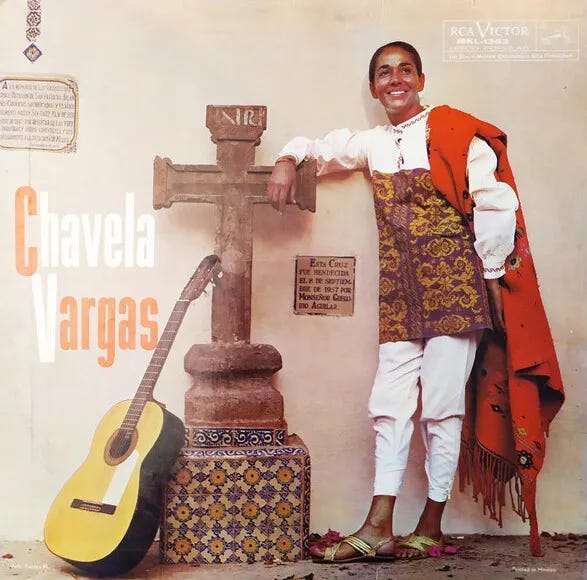

Album of the Day - Chavela Vargas by Chavela Vargas (1961)

May 31, 2024

Witnessing a parent suddenly become emotional and so entranced when hearing a certain type of music, to the point where you can barely talk to them because they’re so immersed, is seemingly a universal experience. My mom comes from some Irish heritage—a few lucky ancestors beat the potato famine—but not in any recent memory. Nonetheless, the plight of the Irish strikes a deep chord within her; sometimes she will simply put on a Celtic folk tune and wistfully sway at the dining room table, eyes shut and all. Among many Mexican parents, it’s ranchera that has that effect as described in this NPR article. It shines light on the bewildering experience of growing up and suddenly the wistful music of your parents’ cultural memory suddenly resonates with you too. Not all folk genres transcend in emotional impact beyond people from the genre’s area, but ranchera is a major exception and one of the hallmarks of Mexican music internationally.

There are dozens of Mexican folk genres, and I’ve covered a few, but perhaps none are as readily identifiable internationally as the ranchera. Ranchera came up at just the right time to solidify its foundation in Mexican national musical identity. After the end of the Mexican Revolution in 1920, which successfully dismantled a three decade-dictatorship and consolidated Mexico’s federalism, democratic rights, and national identity, increasing economic opportunity attracted rural people to urban centers. Songs are the most natural companion of any people on the move, so various manifestations of rural tunes became the sound of the city too. Like flamenco’s strategic promotion in Spain in the same period, the Mexican government started funding comedic films with vignettes of the countryside and those rural ranchera songs in national identity building, canonizing the genre in shared historical memory.

Given ranchera’s national presence and capacity to appeal to many Mexicans, it’s a genre that’s fluid in definition featuring a variety of rhythms and styles. Its operational essential, though, is the presence of one or more guitars. If you’re a lonesome, romantic cowboy, an archetype that is often the icon of ranchera, you might just have one. Some of the most well-known rancheras also incorporate mariachi bands. They say everything’s bigger in Texas, but that’s only if you don’t look south: singers like Vicente Fernandez, often called the ranchera king, bear hats that would put Texans’ to shame. These lofty hats inadvertently reflect ranchera’s romantic pining and the swell of emotions that often defines the genre’s vocal performances replete with drama, evidently played up even more due to their multimedia dominance.

Today’s patron ranchera singer Chavela Vargas was able to take a relatively commercialized form and maintain its sense of universal appeal that commercialism engendered while simultaneously making it her own and defying gender stereotypes in the process as a runaway from Costa Rica to Mexico who personified the vision of ranchera’s hardened outlaw, carrying as much romantic danger as country knowledge. It was somewhat of an open secret that she was a lesbian, although she didn’t publicly confirm that she was until 81, who gladly aided in currying rumors that popped up about her from an affair with Frida Kahlo to being blessed with special shamanic powers. For all the riff raff and rumor, her legend was only able to thrive thanks to her irrefutable talent and ability to move listeners with the strength of her delivery. For the tender lyric of “Desdeñosa” she softens her contralto accordingly, but for the standard “La Llorona” she vocally bears the tears of the song’s hauntingly grief-stricken mother like second nature. She blasts out of the solar system with the growls of “Paloma Negra” as she presciently declares that she will live her life freely, her innate self-confidence backing the vocal firepower. It’s a fantastic elevation of ranchera’s aspect as not just a beloved, emotionally evocative genre, but as statements of independence rooted in its post-revolutionary rise to fame.