Genre of the Day - Kundiman 🇵🇭

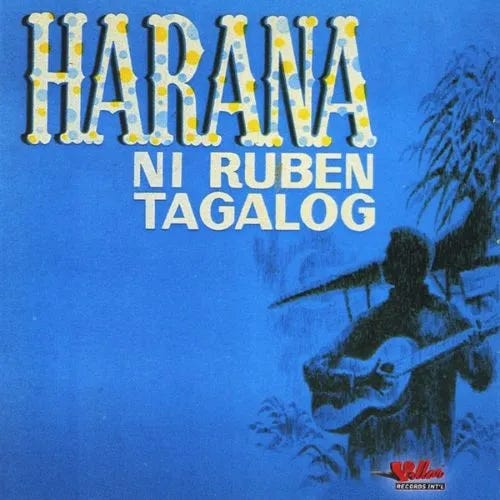

Album of the Day - Harana by Ruben Tagalog (year uncertain; approx. 1950s-1960s)

May 19, 2024

I see much talk online about what it means to be a real lover, or a “true yearner.” Stories of adoration as testaments to the inherent value of overwhelming love, even if its exploits don’t succeed, are a form of currency on Twitter at the moment. While being a lover or a hater might ebb and flow as online phases, love remains a constant in music. Even Darwin suggested that musicality is a trait that developed from sexual selection. And we know why birds sing. Much of music is about interpersonal love and the tangles it entails. It makes sense: what a good lyric can do is illuminate feelings we’re not in a position to articulate as well. Love is one of the most confusing feelings; I can concur that songs are sometimes how I filter my romantic lens.

Interpersonal love can often be a metaphor for the love and appreciation of something much larger though, and this genre encompasses both at a pivotal moment in a nation’s history. We’ve talked about the Philippines a little before in the genre of Filipino Rondalla. Filipino Rondalla was more of an instrumentally-based genre, characterized by ensembles of stringed mandolin-like instruments called bandurrias. Kundiman, on the other hand, is defined by its core lyrical aspects: love and balladry.

Kundiman shares its name with a Tagalog word for a strikingly scarlet piece of cloth; some things about love are universal, and the association with the color red is one. Like the deep red of the cloth, a kundiman song often details the undying affection one feels for one’s partner.

As red also represents anger and the strength of emotion, kundiman also became a component of the musical front of anti-colonial sentiment as the Filipino nation emerged and began to rise up against the Spanish. Spain just won’t stop giving me opportunities to rag on it in this column. As the kundiman gained popularity in the 1870s, red pant-vestiged factions began to signal rousing Filipino nationalism. Kundiman’s insistent musical wells of emotion became tied to exalting the notion of a Philippine nation. A fervent willingness to fight for the motherland became coded in songs about undying love. While love songs can be cast in a simple light, kundiman proves that their possibilities and linkages to shifts in-group cultural sentiment are much larger than what meets the ear.

The red kundiman pants of the katipunan revolutionary factions.

Once the Philippines threw off the Spanish shackles successfully (and had to wait a while for real independence under a greedy US), the kundiman’s connection to the construction of national identity ensured its continued popularity in the 20th century. Today, we’re graced by the King of Kundiman, Ruben Tagalog, whose radio show made him a staple in the 1940s. Over this set of romantic, slow guitar songs, his earnest croon is complimented by the gorgeous, vowel-heavy nature of the Tagalog language that allows his voice to linger, long, and soar on its as and os. While some songs take on a more tragic melodic quality like “Natutulog ka na ba, Sinta?” (Are you sleeping, honey?), the softly unfurled sweet chords of songs like “Harana ng puso” mostly populate the album. With its simple questions, often laid bare by ‘50s heavy vocal echo effects, he demonstrates the undeniable power of simple love songs in their universal aching. On Paraluman, he details it most plainly: “Paraluman ng aking buhay / Nais kong mapakinggan / Na sabihin mo lamang / Na ako ay iyong mahal.” [“Beautiful woman of my life, I want to be heard / That you just say / That I am your love.”]