Genre of the Day - Euskal kantagintza berria (New Basque Song)

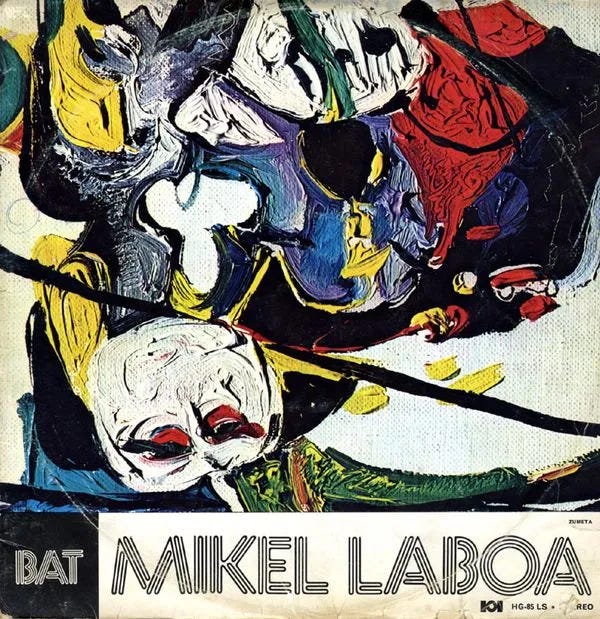

Album of the Day - Bat hiru (One through Three) by Mikel Laboa (1974)

May 12, 2024

Another day, another article ragging on the Spanish and their history of oppression. It just comes up so often in this column. While this has usually been in the context of genres coming out of their colonial history, today’s genre is much closer to home, not on a far-flung continent.

The Basque Country of Spain’s northeast may mostly be known now for its wines and its idyllic city of Bilbao. However, its history stands at the forefront of questions about European nation-statehood, western Europe’s more-recent-than-people-act history of homegrown terrorism, and of cultural and linguistic autonomy. The Basque people speak a language isolate that’s not even remotely related to Spanish and predates the Spanish ancestors’ arrival in the peninsula. Somehow, they remained genetically isolated from the rest of western Europe—despite how messy and dynamic the region’s history has been. This understandably bred a deep, millennia-long cultural insular nature among the Basque people. They were slow to adopt Christianity, and the region has been equally slow to accept Spanish rule. Basque people were historically incredibly good whalers and sailors, an industry that helped prop them up as a reasonably successful home-ruled nation until a series of military struggles in a nationalizing western Europe leading to the Basques losing their sovereign charters in the 1870s.

A cool glow-in-the-dark whale mural in Baiona.

Spanish rule did not exactly prove good for Basque culture, especially under the fascist Franco. The Basque Country had devolved into a complicated, bloody front in the Spanish Civil War immortalized through Picasso’s opus “Guernica,” and the violence lingered in the minds of many Basque people’s historical memory, fomenting deeper sentiments of separatism. Under Franco’s regime, giving babies Basque names was forbidden and public use was strictly discouraged. A narrative formed that Franco was out to wholly stamp out Basque culture, though some argue that his repression was not more particularly brutal than in the rest of Spain. Either way, Basque youth became attracted to both violent means of resistance and more artistic routes. The violent path was the ETA, essentially the Basque IRA who only recently dissolved in 2018 (though they peaked in activity during the mid-1970s) and who injured and killed hundreds of military & governmental targets as well as civilians in a bid to force the Spanish from the region.

Other frustrated Basque activists decided to take it to the booth and the streets. Inspired by the folk genres springing up all across Europe and the US like Catalonia’s Nova Canço, French chanson, and impassioned Americans like Bob Dylan and Joan Baez, Basque musicians began to develop euskal kantagintza berria. They sought to promote Basque culture and traditional songs reappropriated for the folksy wave, and most importantly, sing only in Basque to reunite the Basque population as the youth’s focus began shifting away from Basque culture.

If it’s any indication of the movement’s importance in Basque culture, today’s 1974 album has been called the best in Basque history so you’re really getting the cream of the crop, not just according to RYM users (not always a reliable source) but the opinions of Basque people. Mikel Laboa was something of a revolutionary: he developed a style called lekeitio that made use of onomatopoeias, repetition, and strange sounds, bringing new energy to traditional Basque poems, songs, and children’s tunes.

Laboa’s light voice is beautiful, a perfect canvas to paint these lyrics and unconventional sounds for the Basque audience. The album’s constant emotional shifts reflects the tenuous situation of hope (the jaunty harmonica and scatting of “Pasaiako herritik”) and woes (the plaintive vocal of “Baztan”) the Basques faced. What connects the set is the deep reverence for his culture, and the human need to defend that which is precious through art from forces who seek to strip us of our memories and meaning. He draws many songs from bertsolaritza, the Basque tradition of improvisational songs, connecting himself to a long history of troubadours while extending his own vision with his skills such as taking the children’s rhyme “Baga biga higa” to rapturous heights of intense emotion over the course of eight minutes or in the disconcerting, fragmenting electric strings bookending “Haika mutil.” Basque culture is hard to penetrate, and this album is one of those where to appreciate it best, you’d probably have to be Basque—but nevertheless, it’s a testament to musician’s ability to be a prism for people’s passion and the endurance of ancient cultures against nationalist conformity.