Genre of the Day - Andean New Age

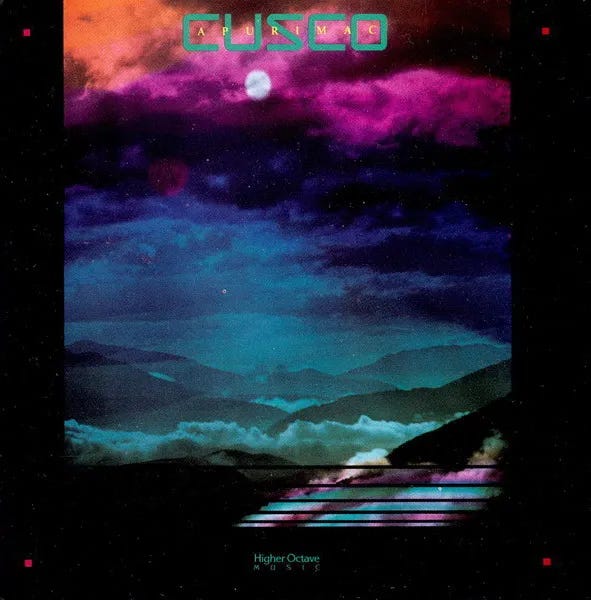

Album of the Day - DOUBLE FEATURE! Apurimac by Cusco (1988) and Inti Watana: El Retorno del Sol by Luzmila Carpio (2023)

June 18, 2024

Move over, weeaboos. Here come Peruaboos.

One rarely ponders the rich interior life of 1980s session musicians. Results of their experiments and somewhat outlandish, globally-minded sonic experiments still linger in today’s world: does Toto’s perennial hit Africa ring a bell? A running theme of this column is just how ingrained the zeal for so-called “world music” was during the ‘80s. I reckon the international breakthrough of reggae did a lot to engender further interest in unknown, marketable sounds from around the globe, and ‘organic’ global sounds represented a compelling contrast to a musical landscape overrun by synthesizers and electrified Frankenstein music. Session musicians had access to the best synths that could evoke any sort of global landscape you wanted, and an age of ‘exotic’ sounding music was born—exotica for the synth and soft rock age.

The breakthrough of “world music”–influenced output by kooky white guys is also indebted to the watery, nebulous concept of New Age music. By the late ‘70s, a variety of that archetype of guy interested in spirituality and music-as-healing started to craft light-infused, meditative albums that echoed the counterculture and mysticism of the ‘60s reconfigured for a decade defined by endless sonic possibility as music-making technology sprung forward. With synths that could imitate unconventional instruments and otherworldly sounds, you no longer needed to learn those instruments or employ their far-off masters: all you needed was an ear for intriguing, soothing melodies and your studio.

Musicians in the New Age scene have looked to ancient, non-Western civilizations as shorthand for ~spiritual vibes.~ It’s certainly not the first and probably not the last time in this column when musicians employed another culture to evoke an air of mystique. Today’s niche takes its sonic inspiration from the hypnotic pan flutes of Andean derivation and the rich, fascinating history of the Andes’ civilizations in creating its vibescape. The majority of musicians who’ve dabbled in Andean New Age are, as you’d expect by now, not of South American descent but rather European musicians. It reminds us of a bygone time in the ‘80s where this sort of culture hopping and paying homage to non-Western musical cultures was seen as cool and innovative.

Questions arise. Is it okay to be making music that sounds like a pastiche of another culture’s rather than elevating music made by people from that culture? Does naming songs after the last Incan king or after the mystical condor glean any spiritual and philosophical insights, or only gesture at the potential to do so by, you know, maybe reading a book about Andean spirituality? Is it clumsy, or actively wrong to exoticize other cultures in painting a picture for your sound? These are not questions I’m built to answer as a genre observer rather than a decider of their validity, but they’re easy to contemplate while learning about this genre. For balance, I listened to two albums today: one by a true New Age outfit and then one by an Andean musician. We find the first repeat visitor to this column in Luzmila Carpio, who is Quechua and appeared in my harawi article, dabbling in infusing traditional Andean music into modern ambient compositions.

Our first album chronologically is by Cusco, a German pair of session musicians Michael Holm and Kristian Schultze. They loved the Incas so much they named themselves after the late, great empire’s capital and title songs after figures like Tupac Amaru and Atahualpa. I can’t say I don’t share the same fascination, and I must recommend a book while we’re at it. The defining musical feature of the set is the synthesized pan flute that’s meant to do a ton of heavy lifting for the whole Peruvian aspect over metallic guitar and soft synth pad flairs.

Groove-wise, though, many of these records are quite danceable: songs like the sloppily-titled “Inca Dance” and “Andes” have more sonically in common with Boney M. than any indigenous Andean music. Their reverence for the pan flute’s timbre does shine through: the melodies are often well-composed, and easy to get lost in, but all of the aforementioned questions end up applying as you come away with as much knowledge about Andean cultures as you would from an Ancient Aliens doc.

Luzmila Carpio’s 2023 set trades in the charango lutes and traditional instrumentation of her traditional harawi for ambient, organic house-esque sounds in order to evoke the grandeur of the Intihuatana, an Incan ritual stone having to do with the sun god and his place in the astronomical calendar. She creates an appropriate, entrancing surrealism such as in the title track’s swirling, windswept metal strings and ominous jaw harp. Oscillating between her native Quechua in which she sings in a stunning, birdlike lilt and Spanish lets her dive into a vast well of musical exploration. She extracts meaning from nature like contemplating the nature of achievement and mortality in the conversation with a dove of “Requiem para un Ego” and aims to become the dove in the range-defying, resplendent “Ofrenda de los Parajos.” The album captures an emotional gravity and contemplative beauty that proves the best insights into Andean spirituality indeed lie here, at the source.