Genre of the Day - Mariachi

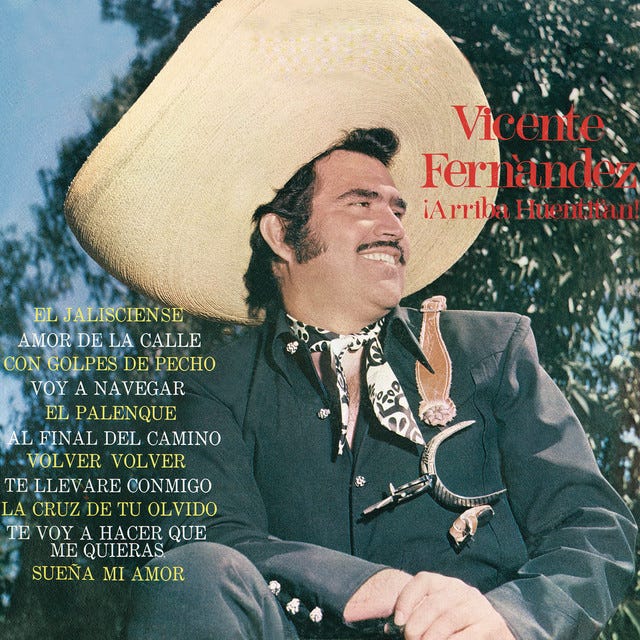

Album of the Day - ¡Arriba Huentitán! by Vicente Fernández (1972)

Is it jumping the gun to commence with another Olympics-themed intro? I’d argue that it’s not. The Games only come every four years, and they’re one of the select events that captures the attention of almost the entire global population. One underrated aspect of the Olympics is that each span of four years allows enough time for a new set of lesser-known sports to weasel their way onto to world’s most heralded athletic stage: breakdancing, sport climbing, and artistic swimming (really synchronized swimming with a more graceful name) caught my eye this year. I propose that Los Angeles’ 2028 Olympics add a new event—competitive big hat-wearing. To elegantly don such a grand cap requires an artistic touch. If today’s artist Vicente Fernández was alive today, he’d certainly take gold.

Another big hat wearer, Zendaya. This massive hat crosses my mind often.

Big hats may not be the central component of mariachi as a music genre, but their statuesque size reflects the music’s grandeur and culturally and sonically-spanning ensemble performances. In a couple of prior articles, I’ve covered the mix of native and Spanish stylistic collisions, African rhythms, and Central European influence introduced through military music, waltzes, and polkas imported during Mexico's brief, retrospectively baffling era under an Austrian emperor in influencing Mexican folk music, but no other amalgamation of those elements has become as symbolic and internationally iconic as mariachi.

Mariachi was borne in the late 19th century of the rolling hills sweeping western Mexico's state of Jalisco, marked by expansive fields of sugarcane, agave, and corn. Surrounding states also lay claim to Mexico’s most famous sound, but Jalisco is where the genre crystallized. Musicians in simple working garb to play a variety of folk instruments communally for the wealthy families of hacienda estates or at their ranches. At the time, four musicians typically figured in the instrumental ensemble, playing the deep six-stringed guitarrón, the ornate five-stringed vihuela, and two violins, though other areas also included the harp. Mariachi’s now-ubiquitous trumpets were only introduced in the early 1900s as mariachi became the music of urbanized national and formal events. Given increasing import, ever-larger groups of mariachi bands dressed in ornate, colorful outfits designed after horsemen.

The 20th century saw worldwide efforts in national branding through showcasing exemplary musical forms considered elegant: post-contemporary Mexico’s choice was mariachi. Its musical capacities were and remain elastic; given that the bands’ sole constant is in instrumental makeup, mariachi groups can adapt to more traditional rural compositions, waltzes, serenades, huapangos, boleros, and corridos. Its majestic fashion and wide yet instrumentally distinctive musical range, bolstered by some aggressive image pushing by the Mexican government, has led to mariachi touching many corners of the globe and remaining a widely performed genre. My high school had a mariachi band, and mariachi bands often feature in the celebrations of the Mexican diaspora since being taken up as a symbol of pride among the Chicano movement of the late ‘60s.

Vicente Fernández was born decades after mariachi became a nationalized, synonymous form, yet his roots reflect those of the genre at its origin. He left school at a young age to help raise cattle on his family’s ranch. In his daydreams, he idolized the singer-actors of the silver screen of his youth. He tirelessly honed his guitar and vocal skills through busking. His efforts paid off a thousandfold as he went on to ascend to mariachi’s biggest star in the late 1960s, assisted in part thanks to his regal hats but mostly due to his emotive, well-appointed tenor. Anchored by the hit “Volver, Volver,” today’s album is a masterful distillation of mariachi’s passion, best experienced in person but still potent on recording. “El Jalisciense” is a rowdy, theatrical ode to mariachi’s origin land, his capable tenor soaring over the horns, bouncing guitar, and swooping strings. The lovelorn cries and tender instrumental of bolero-tinged “Amor de la Calle” positions mariachi’s musical appeal masterfully—Each instrument receives rich solo exploration between skillful full-band choruses. Mariachi is an excellent example of how in ensemble music, each instrument’s contribution to mood and theme stands in equal glory to the sum of all parts. The violins of “El Palenque” zip along, lending the track a propulsion enriched by rapid horn riffs and militaristic snares. The harmonica of “Te Llavore Conmingo,” an atypical instrument in mariachi, nods to the countryside that birthed the genre. The album exemplifies mariachi’s ambitious prism of traditional Mexican sounds, themes, and regional identities with style, as does the breadth of Fernández’ massive hat brim.