Genre of the Day - Welsh Folk Music

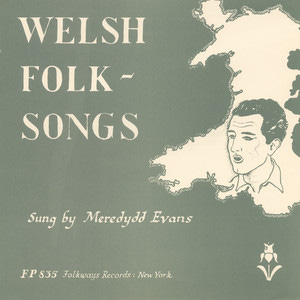

Album of the Day - Welsh Folk Songs by Meredydd Evans (1954)

July 1, 2024

There are a lot of articles periodically circulating on the Internet consisting of ‘untranslatable words.’ Do the articles have any point? They’re cute and fun, and you might learn a thing or two about history through factoids. It’s rare that you ever get to dive in further than that, unless you participated in that weird era a few years ago when people devoted themselves to Danish hygge precepts. One of the words I’ve noticed often crop up in these listicles is the Welsh word hiraeth. It indicates a longing wistfulness for a place or a person to which one can not return, one that causes a deeper churn in your stomach than an English equivalent like nostalgia. Perhaps it resonates so deeply as a symbol of the Welsh nation because Wales’ proud culture and history, like many of the other countries that have now been incorporated into the UK, has fought against the all consuming force of English assimilation and industrialization. Luckily, the Welsh language is now growing in speakers after successful efforts to revitalize the language’s use in public life and the culture was far from ever stamped out. Nonetheless, existing as a culture so often in flux for hundreds of years carries great sorrow. Hiraeth is both the name of a Welsh folk song and a concept infused in Wales’ music; the lyrics longing for the Wales of yore while the act of singing in Welsh asserts the nation’s heritage in the present moment.

Welsh music wears both its Celtic history on its musical sleeve while having evolved with widespread European traditions, as the Celtic nation of the British Isles with the most physical proximity to England and continental Europe besides the tiny cutie Cornwall. The Welsh folk festival eisteddfodau, hosted since Wales was an independent kingdom in 1176, exemplifies Wales’ preeminent love for singing expressed through competition in a sort of Walesovision. On the instrumental side, last week gave me a compelling glimpse into harp handicraft as Paraguay’s national pride and instrument. As the “the strings of [the] nation's heart,” Wales rivals it in its reverence for the instrument. Songs in the cerdd dant tradition follow a harp melody with a counterpoint verse, unique in their unconventional melodies diverging from European dominant melodic ideas as cerdd dant developed. Since Italian harps reached the nation in the 1600, Wales has been a faithful proponent with its signature majestic, light-timbre triple harp jutting forward like a ship’s bow. Wales is also unique for the ancient crwth (pronunced crooth), something of a rectangular violin, and the seal tusk-like pibgorn, a horn that can be played as a bagpipe or by itself, explained in Welsh below.

As you might expect, the use of the Welsh language is of central importance to Wales’ folk music. The 2022 book “A History of Welsh Music” outlines Wales’ innovative system of teachers in the 1800s imparting Welsh language literacy village-to-village, creating a chain of people who could teach the skill unto others and making Wales one of the most literate regions in the world at that point. This stimulated greater engagement with hymnal books and a subsequent rise in choral participation, stitching an even more widespread love for singing into the fabric of Welsh society that became internationally recognized. Welsh singers demonstrated the tradition of eisteddfodau at the 1893 Chicago World Fair, and Welsh immigrants transported the identity of the “Land of Song” worldwide. The persistent use of the Welsh language, a trainwreck alphabetically to English-speaking eyes but enthralling and beautiful sung and spoken, makes Welsh folk music particularly striking as well as bold in its assertion of indigenous and Celtic languages’ relevance.

Welsh, with its many unfamiliar sounds (the potentially spit-producing consonant ll demonstrated in the video below) to English-pilled ears, rings proudly on today’s completely a capella album. Today’s singer Meredydd Evans was a fervent supporter of 20th century Welsh language preservation as a recorder and promoter via BBC Wales TV programs. He hadn’t even intended to release an album with no instrumentation, though. By the time he was a Princeton graduate student in the early 1950s, he’d already become noted for light-hearted close harmony songs in Welsh in the group Triawd y Coleg he’d formed as an undergraduate student. He was approached by Folkways Records, accepted the offer to record some traditional Welsh songs, belted out what he thought was a bunch of demos to provide examples, and Folkways gunned for it as the final product. It’s brilliant in bringing you perhaps closest to the essence of folk music that focuses as much on the people and their history as the actual music at hand; it feels as if you’re sitting in Evans’ kitchen, hearing him sing a tune to himself, background noises and all. His mellifluous but grounded voice carries the weight of “Hiraeth[‘s]” longing with apt heartfeltness. There is a melancholic, poetic quality to most of these fragmented, blink-and-you’ll-miss-them tunes. Nonetheless, sing-songy energizers like “Bachgen Bach O Dincer” (“Little Boy from Tinker”) underscore equal parts joy and wistfulness in celebrating Wales’ vibrant culture and language, a success story for cultural preservation across the past centuries geared towards assimilation.

Nice piece! I went to the annual musical festival in Llangollen a while back (Joan Baez headlined) -- try saying that Welsh town name! -- and have heard people speak Welsh on occasion. Even speaking English, the Welsh accent is so musical. The street signs are in both Welsh and English. It's wonderful that they have committed to preserving their culture, especially the music as you've described.

I had to laugh at "tiny cutie Cornwall." Very funny.