EVERY GENRE PROJECT - January 28 - Romanticism

Genre of the Day - Romanticism

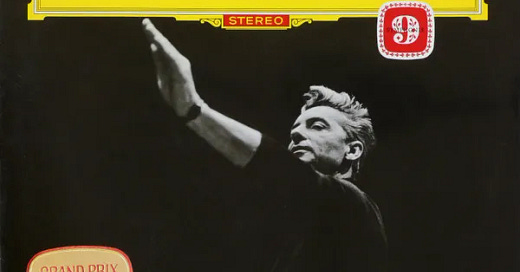

Album of the Day - Symphony No. 9 by Ludwig van Beethoven, as performed by the Berliner Philharmoniker

What do you get for the one who has everything? What does one say about the ‘album’ (if we’re referring to symphonic works as albums, it’s loosely defined, you get the point) that has everything said about it, a piece of music so ubiquitous in western music that anything I say here is simply going to feel like a second-rate Wikipedia entry? I’m not quite sure. However, that’s not a very romantic view, if we’re taking today’s genre name to heart, so I will simply push forth with gusto and as usual yap about that which I listened to today.

Romantic music is relatively straightforward in terms of definition, but deeply meaningful when considering its historical context. It’s music that sounds, well, romantic in a way: flushes of emotion and expressiveness in melody. Romanticism represents a whole new chapter in European music, though; music that emphasizes the individual and emotion, a greater emphasis on melody (which begs the question: what the hell was happening in European music before? How quantifiable is melody?), a wider range of tonal dynamics, and generally a push towards expanding the boundaries of music’s possibility. Perhaps most importantly, these changes came not from a vacuum but because of the extensive social changes occurring early in the 19th century; the middle class was growing rapidly and becoming paying audiences, so composers were free from the constraints of performing only for the aristocracy and catering to their tastes.

That goes quite hard, at least to me. The democratization—to a certain extent—of music, is something to celebrate, although it’s still evolving—in a way that today often makes life harder for artists than it should (more the record companies’ faults than the listeners, but nonetheless). Artists change the music depending on how they have to present it to the audience, and the audience in turn reinforces change by, well, choosing whether to be a paying audience or not. It’s the eternal dialogue of music no matter the genre. However, it’s lovely to think of what music looked like and how composers expanded their sonic ambitions during this transitional, perhaps purer time period of audience consumption.

Of all composers, it’s probably safe to say that no other composer rose to this challenge better than Ludwig van Beethoven, one of the most famous names in music. I have, like probably a solid half of the world population, been exposed to Beethoven at some point. I probably even played some Beethoven on the piano, but I’ve repressed most of my Suzuki memories (so clinical! So boring! But it was always fun to earn a sticker when I completed). However, I don’t think I’d ever exposed myself intentionally to one of his full sets, and while Symphony No. 9, one of his most famous works, sounds familiar across several points, taking it all in at once. It’s astonishing; it feels as if it is constantly building, like witnessing the construction of a musical skyscraper, swooshes of impassioned strings flaring up, but with so many tricks up his sleeve, like throwing in a fully vocal component on the last suite. My layman writing could never really do the trick, but this really is music everyone should listen to at least once; when I place myself in the shoes of what it must’ve been like to receive it for the first time, I am even more impressed, and in a way proud because of its significance as such an avid music consumer myself.