EVERY GENRE PROJECT - February 12 - Australian Folk Music

Genre of the Day - Australian Folk Music

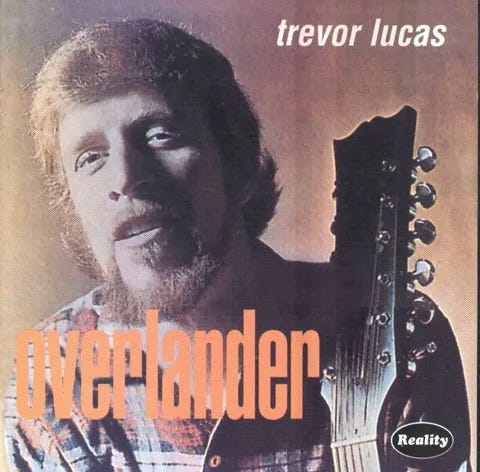

Album of the Day - Overlander by Trevor Lucas (1966)

Another uncanny day on this column arrives. Just last night, I was musing to friends about what life might be like if you solely pretended you lived in Australia while being in the United States, such as only eating fairy bread and vegemite and going surfing every weekend and only listening to Australian music (if you’re a big Kylie Minogue or Bee Gees fan, not too arduous). However, this only works as speculation because Australia doesn’t have that big of a singular cultural reach in the US. Sure, there are some figureheads here: Olivia Newton-John (RIP), Steve Irwin (RIP), Jacob Elordi, Margot Robbie, the recent TikTok collective memory revisit to Iggy Azalea (really, what were you doing at 16 in the middle of Miami). Really, though, how strong can Australian culture be that these figures can just shed their accents and forget what the barbie means in their slang? Just kidding, no hate to the Aussies. But I feel that as a whole, America’s understanding of Australian politics, culture, and history is extremely surface level. It tracks: it’s far as hell, the country only has 25 million citizens, and as part of the commonwealth its overseas ties lie much more with the UK than with us.

Our nation’s histories parallel each other in many ways. They’re both vast nations with a shared memory of pastoralism and conquering an unfamiliar terrain, built on pushing aside the native population, largely at the hands of people from around the British Isles and Ireland and other parts of western Europe with little other opportunity, traveling to vast expanses of unfamiliar land and bringing their musical traditions there. Unlike the US, though, the Australian settler population makeup is much less diverse, largely due to the fact that Australia was little more to the UK initially than a penal colony substitute for the fact that with America’s independence they couldn’t ship away their convicts. And Britain was jailing boatloads (no pun intended) of people, most of whom were jailed for petty crimes out of sheer desperation as they were relegated to the slums of Britain's rapidly industrializing cities. It was better than simply execution, I suppose, although seeing some of those spiders probably made those convicts think they were actually in hell.

In terms of rehabilitation, the opportunity to come to Australia ended up fruitful for many convicts. By the mid 1830s, just a fraction (6%) of convicts were still locked up, and obviously the journey back to Britain was a little arduous so they stayed on in their new land. Their money probably was excellently stretched before the advent of cafés selling $8 lattes throughout the land. Musically, though, the convict system had a massive impact on Australian folk music: the origins of Australian folk music’s sound lies in the importation of sea shanties sung by the convicts on the journey to Australia, which took about three months. There have been many great albums made in less time than that frame, so I imagine with little else to do they developed quite the knack for sharing and creating music. Additionally, it gained unique lyrical characteristics from the slang developed in the outback as many men went into pastoral settings as swagmen (transient labors), stockmen and drovers (cowboys), and shearers (people who cut the wool from sheep).

Trevor Lucas certainly did not live during these times, but like his American and British folk contemporaries harkening back to pre-WWI life following the devastation of WWII he sought to explore that rich history through becoming a folk history. On Overlander, he explores the aforementioned themes of Australian outback life through a variety of folk standards. “The Shearer’s Dream” speaks to the issue of being very womanless and lonely on the outback, a song that had probably persisted for decades because of the tragic gender ratio of convicts (20% women). There’s of course the alcoholic shearer featured on “Bluey Drink.” Some are just odes to the nation, such as “South Australia” and the ubiquitous unofficial Australian anthem “Waltzing Matilda.” Across all tracks though it’s clear that the folk music disproportionately takes after traditional Celtic music, with most songs featuring a fiddle and the guitar with the plaintive melancholy feel of much Irish folk music. No wonder Trevor Lucas ended up finding more work (and love with Fairport Convention’s Sandy Denny) in England despite these obviously Australian-centric themes; his popularity in his native country never quite eclipsed that of his in England, which makes sense: the idea of another country’s music can be quite tantalizing, but in the home country, it might just be too ubiquitous to be interesting. Either way though, this album offers a great introduction into Australian history, so pull out your best wool and a pint to listen.