Genre of the Day - Santería Music

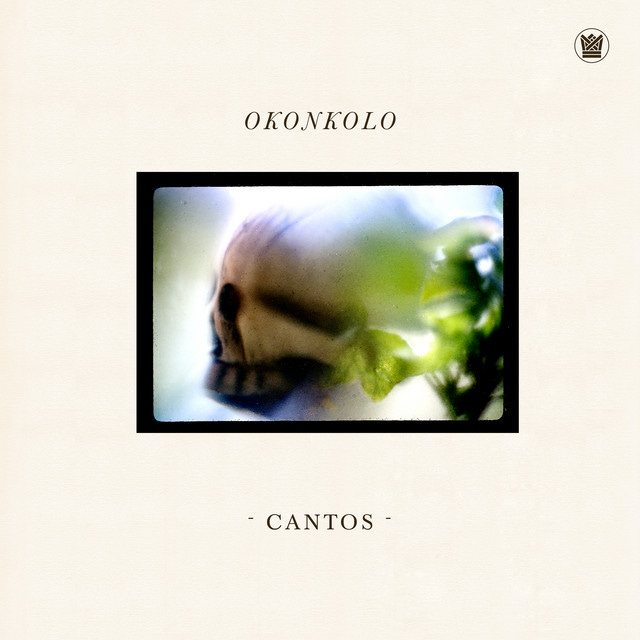

Album of the Day - Cantos by Okonkolo (2018)

The first musical reference to the religion of santería to come to many people’s mind is no doubt Sublime’s 1997 hit, Bradley Nowell musing: “I don't practice Santeria / I ain't got no crystal ball.” Desperate heartbreaks call for desperate measures, and the song invokes the mystique of the opaque practice. Given all the sensationalism around the traditional Afro-Cuban religion, tokenized as a form of occult magic and lumped in with other Afro-Atlantic syncretic practices like vodou, there’s an underemphasis of more nuanced and deeper exploration of the religion’s cultural expression. Today, we delve into the music that goes with its sacred practices.

Music is central and holy in santería practices. The religion employs drums that can be directly traced back to those of Yorubaland in Nigeria, similar to the multi-tonal talking drums that lend musical depth quite unlike any other instrument to genres like jùjú. In the santería ritual setting, the batá drums coax orishas, the hundreds of divine spirits to pay the practitioners an earthly visit. These two-sided drums, led by the largest iyá drum and followed by the itólele and the smallest okónkolo in particular toque rhythms, initiate figures in the ritual into a trance. The bailarín dancer is the key participant of interest, whose deep possession courtesy of the toques allows them to be a vessel for the spirit of an orisha.

Santería music is sung in the Lucumi liturgical language which is descended from the Yoruba language though with a few minor differences as a result of the slave trade severing ties. The akpwón acts as the master of the ceremony and lead vocalist, coordinating the prayer and the ritual with a chorus. Santería musical practices have transfixed filmmakers and recording companies since the international explosion of popular forms of Cuban music in the mid 20th-century, such as in the 1957 Cuban-Mexican joint venture Yambao that depicts a historicized version of santería practices in riveting Technicolor. Santería practitioners and music suffered as a result of stigmatization under state-sponsored atheism following Cuba’s Communist revolution, but santería recordings still found an international audience among those curious about peering into a religion noted for its many closed practices. On YouTube, one can find a wealth of songs devoted to specific deities, like this one dedicated to Eshu Elegua who is considered the patron spirit of crossroads and chance.

Okonololo, which draws its name from santería’s smallest drum, describes the group’s musical project on its Bandcamp in a way that’s tailor-made for a music publication: “a spiritual dance with gods beyond our grasp, held together by rhythm, passion, and musical virtuosity.” They add avant-garde classical flair to complement the music, to often rapturous effect. In “Yemaya,” strings surround and augment the revelatory nature without detracting from the potent performance by the akpwón and the ever-evolving drum patterns. In “Wolenche Por Chango,” a psych guitar line recalls cross-continental African guitar genres like King Sunny Adé’s jùjú, boldly drawing a line between santería traditions and the popular Yoruba music of the last century. A dramatic clarinet and string suite end the song on an ambiguous, but resoundingly beautiful note, fit for the title’s orisha associated with lightning and dance. The album ends with a song to Elegua, as all roads lead to him. Music opens worlds of understanding, just as Elegua is known to open the door as a mediator between practitioners and the other orishas. Today’s genre is a reminder of how amazing it is that recording allows us to experience beliefs in their real-time musical expressions.