Genre of the Day - Fijiri

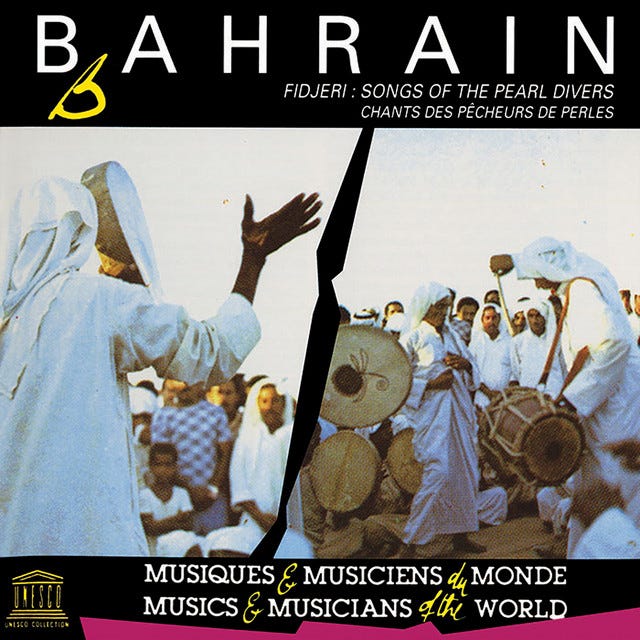

Album of the Day - Fidjeri, Songs of the Bahrain Pearl Divers by the Men’s Choir from the Dar Jnah in Muharraq (1978)

The best things in life may be free, but the most dazzling ones are far from being so. The industry of blood diamonds is well-discussed, but we often forget the human toll exacted in extracting all of those frivolous, shiny things with no inherent purpose other than their beauty. The pearl is the most mystical of all. They’re not of the earth in the same way other gems are, and their iridescent and stunning nature is only accentuated by their banal origins as a defense mechanism for oysters.

The pearl industry had its own human cost, and in the gleam of the gems we easily forget the ways people had to suffer for those spoils (at least Sade remembers). Pearls powered the riches of the kingly states, particularly Bahrain, surrounding the Persian Gulf before oil’s profitability made pearls look like gravel. Though he was far removed from their extraction, Sheikh Muhammad bin Thānı̄ of Qatar remarked in 1863 that the country was “slave to one master—the pearl.” Thousands of hunters, including both local men from the kingdoms and actually enslaved East Africans, endured the isolating work of enriching merchants for months at a time.

When they weren’t braving the daily dives to the seafloor to hope for the one-in-one-hundred chance of discovering a pearl, they found boat-bound catharsis in a form of polyphonic singing as vast and deep as the sea and as mystically-derived as a pearl. One legend of fijiri goes that three wayward travelers discovered a mosque inhabited by jinns, supernatural creatures figuring deep in the mythic histories of the Arabian Peninsula, who revealed the form of singing to them. Different fijiri songs helped ease particular aspects of the back-breaking ship work and create much-needed morale. Like a musically-blessed coxswain, one member of the party was honored with being the nahhām, the soloist who led the work-weary songs with the anguished melisma characteristic of much traditional Arabic music. Diametrically opposite to conventional regional sounds is the wall of sound created by the droning voices of singers beneath, anchoring the nahham’s wide-open ship to the foreboding ocean floor. Fijiri performances take place at dar houses, the gathering place on land between weekly expeditions. They seem a cultic ritual known only my unwilling initiates into the sea’s mysteries, accompanied with dense percussion and unique dances that mimic both healing the body and the movements of diving.

O how I suffer from the long nights

Witnessing those motherless divers

Every time a month passes by, another follows

Until the eyes grow old

The music of the pearl divers miraculously survived thanks to efforts in cultural preservation, as the tradition looked like it would drown as oil took over and uprooted the pearl industry. Today’s recording plunges us into the dark waters, and it’s a moment in this column I can attest to feeling wholly otherworldly. It’s astounding how the singers can coordinate such melismatic rises of their voices like suddenly rising, undulating ocean waves. In “Khrab, Sidi, Meydaf, Jeeb,” the nahhām captures stunning passion in his cries as if physically releasing the pain of every single member of the expedition, as the deep choir of basses cements a floor—as the song moves through different suites representing different moments of the seafaring life, unexpected metal tines and handclap bonanzas join in. Each song moves with total unfamiliarity—breaks into new chants and patterns are as sudden as the winds’ shifts. It is said that pressure creates diamonds, but the danger of the ocean creates transcendental layers of sound gleaming with more beauty than any pearl necklace.

Fantastic, Reid! A brilliant and challenging undertaking. So appreciated by this old Yank!